Docker: VMs, Code Migration, and SOA Solved

It’s rare that a piece of software as new as Docker is readily adopted by startups along with huge, well established companies. dotCloud, the company that created and maintains Docker, recently nabbed $40 million in funding. Microsoft also announced on 11/18 a Docker CLI for Windows. Docker will also play a central role in Azure as well as the next release of Windows Server.

So what is all the hype about?

Docker solves two of the most difficult problems in deploying software: painlessly spinning up VMs, and bundling together application code with the deployment environment.

Spinning up new, customized instance is as easy as a click of a button. Migrating code between platforms is trivial because our application code is packaged with its environment.

We at Keyhole have been seeing a lot of traction around Docker in the past few months. We currently use it in one of our applications to manage our deployment process. The reasons we’ve seen the flurry of activity of it will become clear after I go into what separates Docker from other hypervisors and deployment tools.

VMs on Steroids

Virtual Machines (VMs) are an amazing tool that has helped further abstract the runtime environment from the physical hardware. VMs, unfortunately, come with a pretty steep performance penalty on startup and execution.

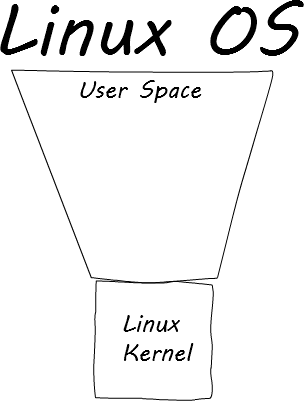

The reason for most of the problems in VMs is a duplication of work. To understand this duplication, think of the structure of the Linux operating system. There is a clear separation between the Linux kernel, which manages deep-level tasks like networking and threads, and user space, which is everything outside of the kernel.

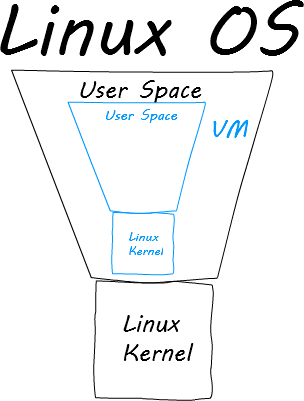

Traditional VMs like VirtualBox and VMWare run their VMs in the user space. When a traditional VM starts an instance of the machine, it spins up a Linux kernel and user space inside of an existing user space.

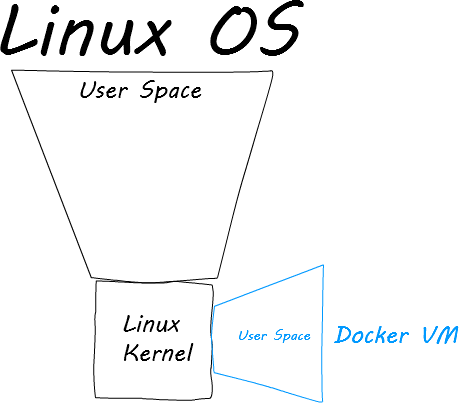

This is where the duplication comes into play. Why should the Linux kernel be inside of a user space when there is already a Linux kernel for it to use? It doesn’t. That is what the makers of Docker realized. As long as the Linux kernel of the VM matches that of the host machine, there is already a clear separation that the VM user space can take advantage of.

When a Docker VM starts up, it attaches the VM user space to the host Linux kernel. This means that boot happens in a manner of milliseconds. The performance is 97% of software running on the host machine. Docker has all of the advantages without any of the drawbacks. Plus…

Deployment Solved

A Docker VM is generated from a well-defined script called a Dockerfile. The Dockerfile specifies what flavor and version of Linux to use, what software to install, what ports to open, how to pull the source code in, etc. Everything you need is bundled together in one file. This is an example Dockerfile from a project I did a few months ago:

FROM ubuntu:12.04

MAINTAINER Zach Gardner <zgardner@keyholesoftware.com>

# Update apt-get

RUN apt-get update

# Create container

RUN mkdir /container

RUN mkdir /container/project

# Install NodeJS

RUN apt-get --yes install python g++ make checkinstall fakeroot wget

RUN src=$(mktemp -d) && cd $src && \

wget -N http://nodejs.org/dist/node-latest.tar.gz && \

tar xzvf node-latest.tar.gz && cd node-v* && \

./configure && \

fakeroot checkinstall -y --install=no --pkgversion $(echo $(pwd) | sed -n -re"s/.+node-v(.+)$/\1/p") make -j$(($(nproc)+1)) install && \

dpkg -i node_* && \

rm -rf $src

# Install NPM

RUN apt-get --yes install curl

RUN curl --no-check-certificate https://www.npmjs.org/install.sh | sh

# Install Bower's dependencies

RUN apt-get install --yes git

# Install PhantomJS dependencies

RUN apt-get install --yes freetype* fontconfig

# Move source code to container

ADD / /container/project

# Install NPM dependencies

RUN cd /container/project/ && npm install

# Install Project's Bower dependencies

RUN cd /container/project && (echo -e "n" | ./node_modules/bower/bin/bower install --allow-root)

# Compile code

RUN cd /container/project && ./node_modules/grunt-cli/bin/grunt build

# Start server

CMD /container/project/node_modules/grunt-cli/bin/grunt --gruntfile /container/project/Gruntfile.js prodThe first thing I do in this script is define that I’m using Ubuntu 12.04. I install NodeJS, NPM, and git. I copy my source code from my repository, download the runtime dependencies, compile my code, and start my server.

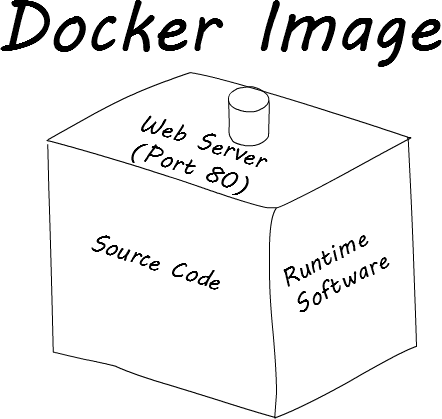

When you pass a Dockerfile to Docker, it generates a Docker image. The best way to think of a Docker image is that it is a self-contained zip file that contains everything an application needs to run.

The source code and execution environment being combined is a complete paradigm shift from traditional deployment methods. Rather than moving code, having a human execute shell scripts to update the environment, and wishing for the best, you can instead transition fresh Docker images to the different platforms. There is virtually no human intervention required, which reduces the chance of mistakes. Best of all is that once the QA’s have signed off on a specific version of the application, you can be sure that application won’t change as you migrate it up platforms.

Interestingly, the Docker paradigm of transferring Docker images falls inline with some of the research that’s been done in Reactive programming. Managing state is one of the most difficult things to do in an application. Mutability makes creating thread-safe code a non-trivial job. By shifting the thinking over to process immutable pieces of data, the CPU is allowed to optimize threads and operations in a much easier manner than before. Docker follows that paradigm by getting rid of the concept of software updates on platforms. It is much easier to scrap the running Docker image and replace it with a new one than to worry about how to upgrade the current running image. No scripts are necessary to upgrade things like Java if the version is out of date, or other worrisome things like that. Docker takes the guesswork out of what software is running on your platforms: it’s what ever the developer specified in the Dockerfile.

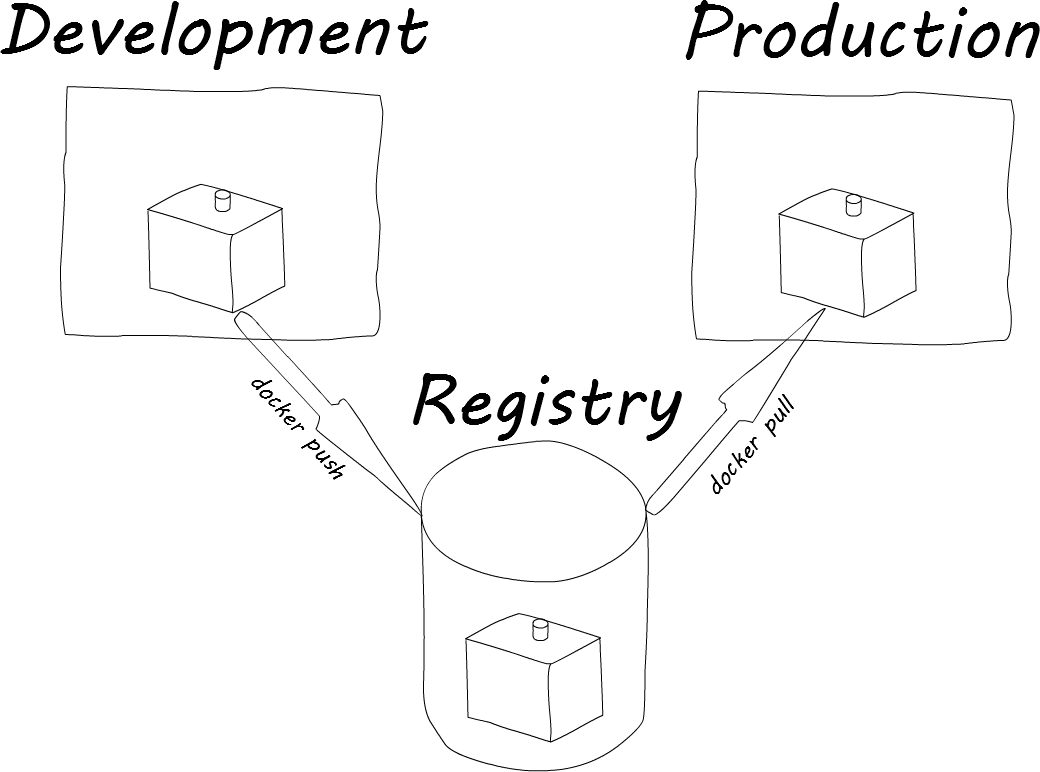

Migrating the image across platforms is a trivial job. Docker images can be pushed to a Docker registry (public or private), and pulled down onto the desired platform. The syntax is very similar to git:

On a development platform

docker push zgardner/myapp

On a production platform

docker pull zgardner/myapp docker run -i -t zgardner/myapp

In the example above, I first pushed myapp up to a Docker registry. I then pull it down from a higher platform, and run it.

The term for a running Docker image is a Docker container. There are some steps that I omitted to show the shutting down of the existing container, how to specify the port on which the Docker container should communicate through, etc. Those are things though that the organization that uses Docker can specify for themselves.

The idea of being able to migrate code so easily is a welcome revolution compared to every in-house, proprietary, home-brewed solution I’ve ever seen. Combining the power of a Linux-kernel attached VM with a simplified migration process has some pretty powerful ramifications. We at Keyhole have been experimenting with CoreOS and Fleet to deploy new servers, set them up with Docker, and download Docker images all from the Amazon AWS console. We’re also starting to experiment with…

Service Oriented Architecture: Easy as Sliced Bread

Docker is the first true DevOps tool. It allows developers to easily specify the environment in which their code should be executed. It also removes the stress of worrying about upgrading the environment.

Docker images being static containers means they need to offload persistent data outside of the application itself. This is commonly done by mounting an AWS drive when defining the Docker container. This also means that the code contained inside of the application needs to be small, concise, and very focused. Because the application will run inside of an isolated environment, it needs to be defined as if it can be ran on an island by itself.

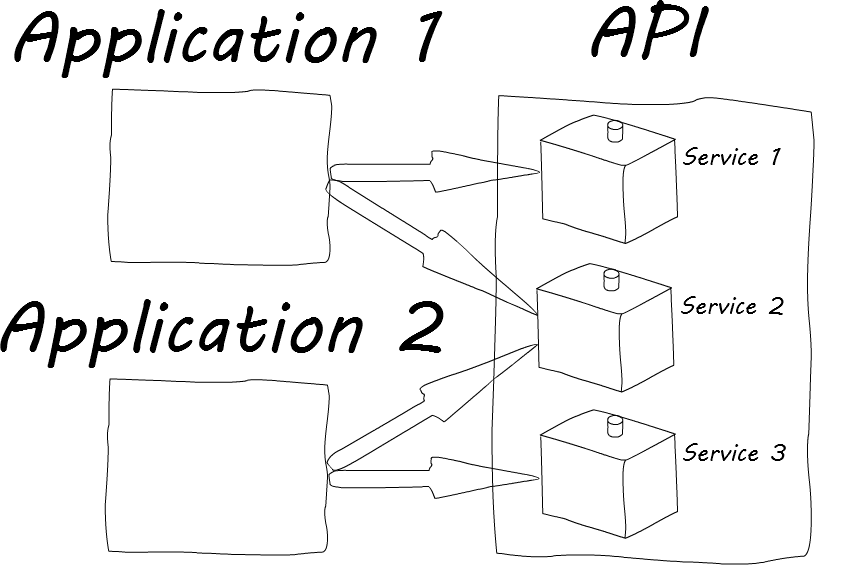

That tends to lend itself very well with a SOA (Service Oriented Architecture). A SOA is a different way of thinking about an API and how applications in general are composed. The traditional way of thinking of an application is that it is a system composed of smaller technical parts. These technical parts may be things like Products or Customers or Funds or cron jobs. Some of these technical parts may needed in other applications that a software company has written. The traditional approach is to either try sharing the code, which often doesn’t work because it was written with only the original application in mind, or copying the code all together, which really doesn’t work.

An application written with a SOA in mind is designed with a completely different goal in mind. In a SOA, applications are pieced together by composing business needs together with application code. Some of the technical parts mentioned above are actually business needs. These tend to be the same across applications, though they may be used in different ways depending upon the UI. If each of these business needs can be siloed into a well-defined, consistent interface, they are reusable by design.

Making a SOA a primary focus of an organization allows new applications to be pieced together quickly and effectively. Amazon was one of the first companies to pioneer this approach. SOA is catching on with a lot of other small and large companies because it works so well.

Docker lends itself very nicely to a SOA. Each service can be conceived of as a separate Dockerfile. Migrating the services across platforms is as easy as pushing a static Docker image and pulling it down. They are isolated by their very nature of running in an independent VM. Using API documentation tools like Swagger can help make the service even more well defined.

Docker is also used by companies like Netflix to implement micro-services. These services are different than traditional services in a SOA by their scope. Traditional services have a lot going on, and are often difficult to isolate and contain. Micro-services focus on extremely small, reusable components that have as little knowledge of their environment as possible. The isolation that Docker gives works well with enforcing tiny micro-services that can be deployed anywhere.

At Keyhole, we’re working to rewrite our Q&A system along with our Timesheet application to use a SOA with Docker. The results have been very promising so far. We have future blog posts that will detail different things we’ve found out and experienced during this process.

To Wrap It All Up

Docker is a very powerful tool that we believe will be an industry standard within the next few years. It flips the VM and application migration process on its head. It will be exciting for us to help clients implement it in their stack, and see serious savings in time and energy. Docker will allow developers and enterprise system engineers to stop worrying about build and deployment issues, and instead focus on what matters: building beautiful applications.

| Reference: | Docker: VMs, Code Migration, and SOA Solved from our JCG partner Zach Gardner at the Keyhole Software blog. |