Are You Binding Your Oracle DATEs Correctly? I Bet You Aren’t

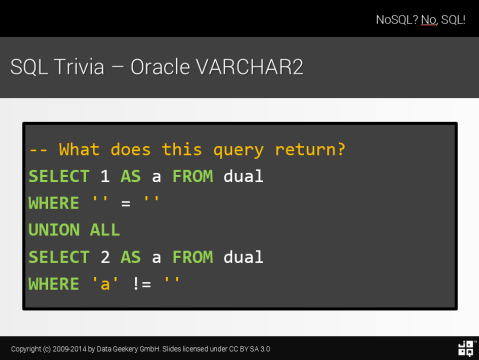

Oracle database has its ways. In my SQL talks at conferences, I love to confuse people with the following Oracle facts:

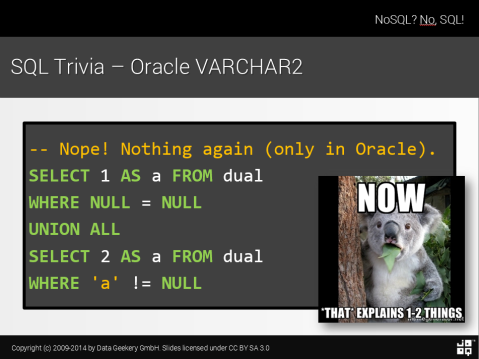

… and the answer is, of course:

Isn’t it horrible to make empty string the same thing as NULL? Please, Oracle…

The only actually reasonable slide to follow the previous two is this one:

But the DATE type is much more subtle

So you think VARCHAR2 is weird?

Well, we all know that Oracle’s DATE is not really a date as in the SQL standard, or as in all the other databases, or as in java.sql.Date. Oracle’s DATE type is really a TIMESTAMP(0), i.e. a timestamp with a fractional second precision of zero.

Most legacy databases actually use DATE precisely for that, to store timestamps with no fractional seconds, such as:

- 1970-01-01 00:00:00

- 2000-02-20 20:00:20

- 1337-01-01 13:37:00

So, it’s always a safe bet to use java.sql.Timestamp types in Java, when you’re operating with Oracle DATE.

But things can go very wrong when you bind such variables via JDBC as can be seen in this Stack Overflow question here. Let’s assume you have a range predicate like so:

// execute_at is of type DATE and there's an index

PreparedStatement stmt = connection.prepareStatement(

"SELECT * " +

"FROM my_table " +

"WHERE execute_at > ? AND execute_at < ?");Now, naturally, we’d expect any index on execute_at to be a sensible choice to use for filtering out records from my_table, and that’s also what happens when we bind java.sql.Date

stmt.setDate(1, start); stmt.setDate(2, end);

The execution plan is optimal:

----------------------------------------------------- | Id | Operation | Name | ----------------------------------------------------- | 0 | SELECT STATEMENT | | |* 1 | FILTER | | | 2 | TABLE ACCESS BY INDEX ROWID| my_table | |* 3 | INDEX RANGE SCAN | my_index | ----------------------------------------------------- Predicate Information (identified by operation id): --------------------------------------------------- 1 - filter(:1:1 AND ""EXECUTE_AT""<:2)

But let’s check out what happens if we assume execute_at to be a date with hours/minutes/seconds, i.e. an Oracle DATE. We’ll be binding java.sql.Timestamp

stmt.setTimestamp(1, start); stmt.setTimestamp(2, end);

and the execution plan suddenly becomes very bad:

-----------------------------------------------------

| Id | Operation | Name |

-----------------------------------------------------

| 0 | SELECT STATEMENT | |

|* 1 | FILTER | |

| 2 | TABLE ACCESS BY INDEX ROWID| my_table |

|* 3 | INDEX FULL SCAN | my_index |

-----------------------------------------------------

Predicate Information (identified by operation id):

---------------------------------------------------

1 - filter(:1:1 AND

INTERNAL_FUNCTION(""EXECUTE_AT"")<:2))What’s this INTERNAL_FUNCTION()

INTERNAL_FUNCTION() is Oracle’s way of silently converting values into other values in ways that are completely opaque. In fact, you cannot even place a function-based index on this pseudo-function to help the database choose a RANGE SCAN on it again. The following is not possible:

CREATE INDEX oracle_why_oh_why ON my_table(INTERNAL_FUNCTION(execute_at));

Nope. What the function really does, it widens the less precise DATE type of the execute_at column to the more precise TIMESTAMP type of the bind variable. Just in case.

Why? Because with exclusive range boundaries (> and <), chances are that the fractional seconds in your Timestamp may lead to the timestamp being stricly greater than the lower bound of the range, which would include it, when the same Timestamp with no fractional sections (i.e. an Oracle DATE) would have been excluded.

Duh. But we don’t care, we’re only using Timestamp as a silly workaround in the first place! Now that we know this, you might think that adding a function-based index on an explicit conversion would work, but that’s not the case either:

CREATE INDEX nope ON my_table(CAST(execute_at AS TIMESTAMP));

Perhaps, if you magically found the exact right precision of the implicitly used TIMESTAMP(n) type it could work, but that all feels shaky, and besides, I don’t want a second index on that same column!

The solution

The solution given by user APC is actually very simple (and it sucks). Again, you could bind a java.sql.Date, but that would make you lose all hour/minute/second information. No, you have to explicitly cast the bind variable to DATE in the database. Exactly!

PreparedStatement stmt = connection.prepareStatement(

"SELECT * " +

"FROM my_table " +

"WHERE execute_at > CAST(? AS DATE) " +

"AND execute_at < CAST(? AS DATE)");You have to do that every time you bind a java.sql.Timestamp variable to an Oracle DATE value, at least when used in predicates.

How to implement that?

If you’re using JDBC directly, you’re pretty much doomed. Of course, you could run AWR reports to find the worst statements in production and fix only those, but chances are that you won’t be able to fix your statements so easily and deploy them so quickly, so you might want to get it right in advance. And of course, this is production. Tomorrow, another statement would suddenly pop up in your DBA’s reports.

If you’re using JPA / Hibernate, you can only hope that they got it right, because you probably won’t be able to fix those queries, otherwise.

If you’re using jOOQ 3.5 or later, you can take advantage of jOOQ’s new custom type binding feature, which works out of the box with Oracle, and transparently renders that CAST(? AS DATE) for you, only on those columns that are really relevant.

Other databases

If you think that this is an Oracle issue, think again. Oracle is actually very lenient and nice to use when it comes to bind variables. Oracle can infer a lot of types for your bind variables, such that casting is almost never necessary. With other databases, that’s a different story. Read our article about RDBMS bind variable casting madness for more information.

| Reference: | Are You Binding Your Oracle DATEs Correctly? I Bet You Aren’t from our JCG partner Lukas Eder at the JAVA, SQL, AND JOOQ blog. |