CQRS and Event Sourcing for dummies

CQRS (Command and Query Responsibility Segregation) and Event Sourcing are concepts that are not new at all. Alongside NoSql, Functional Programming and Microservices, these revival concepts are getting traction because of their ability to deal with modern software challenges. Assuming that you’re building a product that has a complex domain with a significant amount of users I can predict that if you follow more traditional architectural styles you will face the following problems &em; how to scale and how to deal with complexity.

Basic concepts around CQRS

CQRS and Event Sourcing address those concerns with an architectural style that, not only works, but makes sense without too much cognitive effort required. Over the past few weeks some colleagues and I have taken part in a study group on Greg Young online tutorial on CQRS and Event Storming. The video is really long, so I’m going to highlight some of the key concepts that fell out of the tutorial, but I’d recommend investing the time to watch it yourself.

CQRS is based in Bertrand Meyer’s CQS (Command-Query Separation) concept. CQS states that every method should either be a command that performs an action or a query that retrieves a result. The concerns shouldn’t be mixed. From a functional point of view that means that query methods shouldn’t have any side effects &em; that is, they’re referentially transparent so we can use them in any part of our system without any contextual knowledge. This approach assists in creating software that is modular and easy to reason about it.

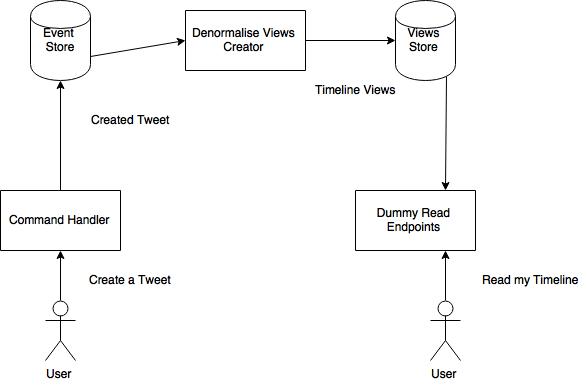

CQRS brings that concept into an architectural level. We shouldn’t be creating services with command and query concerns mixed. This approach is orthogonal, creating different services around bounded contexts. Additionally, any ‘microservices’ should be split in write and read components too. I’m going to provide an example to make it easy to understand.

Challenges of non-CQRS architectures

Let’s imagine that we’re modeling a really small slice of Twitter. A user can tweet, favourite a tweet and read a timeline. In a non-CQRS design we could model the systems around nouns and CRUD (Create, Read, Update & Delete) verbs. Those verbs/actions could be represented as REST (Representational State Transfer) interfaces and normalised tables in a relational database. This kind of structural model offers some problems:

- Write and read concerns are mixed, so the code is harder to reason. We use ORM (Object Relational Mapping) tools like Hibernate for read and write entities that when mixed can be difficult to maintain and understand.

- Managing change is difficult. It’s arrogant or naive to think that we created our model right the first time, so we need an architecture that is easy to change.

- Certain queries to that system could require joining different tables which may prove problematic at a larger scale. Normalised models are suitable for optimising writing scenarios; you just need to write in a single table without having to worry about propagating changes between different denormalised views. They also save storage space for obvious reasons. Nowadays memory is cheap and to be honest, most of the apps that I’ve worked in the past read more than write.

Benefits of getting into an event world

Behavioural modeling is a CQRS alternative to meeting these challenges. Alberto Brandolini created a technique called Event Storming that allows you to model your system in a CQRS fashion. This approach tries to model your system as humans would, or as the business would see it: a flow of commands and events. A command in our example would be Create a Tweet and the event, always in past tense, would be Created Tweet. A command can generate different events and per event we can have different consumers of it. That means that we have flexibility to change our read side, like Read a Timeline, in the future.

This is one proposal that separates write and read concerns and uses event sourcing. It’s important to note that depending on the constraints and challenges of our domain we might design this architecture slightly differently. We could decide to place the event queue at the beginning of our system or we could move some time-consuming tasks into the dummy reader as real Twitter is doing for some special cases. Regardless, some key benefits can be obtained:

- We can scale out easily. Nowadays event queues are beasts. Kafka is used as event store in massive places like Linkedin.

- We’ll face eventual consistency. This architecture follows the fire and forget command style. When we send a command to the system, we don’t wait synchronously for a response. The queue is inherently asyncronous, so the user will have to wait some time until the denormalised view gets updated. Greg Young argues that every system is basically eventual consistent, and is just a matter of magnitudes. The suggested solutions are educating users and, why not, programmers. Programmers often think that their systems are more critical than what reality says.

- We can use different technologies for write and read storage. I’ve already suggested Kafka as an event store (backed for instance by HDFS when you need to archive the events) and you can use Cassandra or Redis for storing the views. Remember that with this architecture you don’t need to calculate the views on read time, so you don’t need to join tables, being that a usual bottleneck.

- We never have to delete or update events (and no longer require the ‘UD’ in ‘CRUD’). We don’t need to synchronise resources as our event store is immutable. If we want to unfavourite a tweet, we send a command that will publish a Unfavourited Tweet in our event store. This will trigger a recalculation of our timeline view removing that favourite action in the tweet.

But what happens when you reach millions of events? Do you need to replay every single event every time you get a new event in the system? The answer is snapshots. Periodically we’ll store snapshots of our views and persist them. Along with that snapshot we’ll record the pointer (offset in Kafka) of our topic so we know that that when the snapshot was taken. Whenever we need to replay the events to reconstitute our views we can do it from a chosen snapshot and not from the beginning of the time.

Why would we want to replay events? One important reason is to help us create irreproducible bugs. Often bugs are hidden in specific combinations of system state and ican become difficult hard to emulate when the system is complex. If the user can send a report that includes the command and hence the event that caused the bug, we can replay the system to that specific point in time in an effort to ascertain the cause of that damn bug.

In conclusion

I really believe that this architectural style removes accidental complexity from systems that are unable to scale as modern world requires. The world changes and software has to keep up. So, despite of the hype, event driven architectures, microservices, NoSql and functional programming are here to stay. They provide new ways to tackle difficult challenges in software operations and testing resulting in what is potentially, an exciting time for programmers everywhere.

| Reference: | CQRS and Event Sourcing for dummies from our JCG partner Felipe Fernandez at the Crafted Software blog. |

Very good post, it was usefull.

I found this open source project really good to understand the concepts of CQRS and Event sourcing. Seems like is work in progress, but the code base and unit test help me a lot to understand the ideas.

https://github.com/politrons/Scalaydrated

Although I agree than Kafka is useful for event sourcing for example being used as event publisher, I don’t understand how Kafka can be used as event store. Event store should have key-value structure so that we can prevent concurrency problems and improve event query performance. Does Kafka have features that support it?