Agile Myth #7: “Agile Means No Documentation”

The Agile Manifesto says, “Working software over comprehensive documentation”, and many people assume that Agile means little to no documentation. That’s not true. A well-run Agile project actually produces a lot of documentation. The difference is that Agile practitioners are conscious to create documentation that is actually readable & useful. Common sense, right? But for a lot of software development veterans, we know that projects often produce a lot of documentation that are a waste of time and effort, because they provide little help in the creation and long-term maintainability of the software.

Agile improves on documentation in two ways:

- Documentation happens after conversations.

- Words alone often lead to misunderstanding. Just passing documents around denies stakeholders & developers the opportunity to have rich discussions on how to build optimal solutions. Documentation is important to remind us of what was agreed, but the conversations have to come first before the documentation.

- Documentation is weighted towards examples & test cases.

- Stakeholders & developers often get into arguments over their interpretation of requirements. That’s expected, since there are often many ways to interpret a written phrase. For example, if a restaurant menu says that a dish comes with “soup or salad and bread”, do they mean: “dish + (soup OR (salad + bread))” or did they mean “dish + (soup OR salad) + bread”? Agile strives to remove ambiguity by providing examples and test cases. Discussions between and among stakeholders and developers become more precise when they discuss examples and test cases.

Below is some more discussion on how requirements documentation and technical documentation are often wasteful, and the Agile alternatives:

Requirements Documentation

Typical project methodologies strive to avoid change, so they attempt to define all requirements upfront. For any large project, however, stable requirements are impossible. For one, business needs often change in the middle of the project – whether they be because of competitive pressure, regulatory changes, or changing customer preferences. The other reason is that project stakeholders don’t really know what they need until they see and use a system. The only time they realize that they specified wrong requirements is when they actually give the system a test-drive, and this is usually towards the end of the project.

Typical project methodologies strive to avoid change, so they attempt to define all requirements upfront. For any large project, however, stable requirements are impossible. For one, business needs often change in the middle of the project – whether they be because of competitive pressure, regulatory changes, or changing customer preferences. The other reason is that project stakeholders don’t really know what they need until they see and use a system. The only time they realize that they specified wrong requirements is when they actually give the system a test-drive, and this is usually towards the end of the project.

Further compounding the problem with requirements documentation is that words on paper are not enough to convey the intent of the stakeholders to the development team. The development team goes and builds everything in the requirements, but when they present what they’ve built to the stakeholders months or years later, everyone realizes that the requirements have been misunderstood, and have built something unusable to the stakeholders, even if the developers complied with the requirements to-the-letter. The blame game then begins, with stakeholders blaming the developers for their poor understanding, and developers blaming stakeholders for poor documentation.

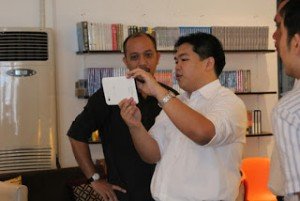

Some of you who are already familiar with Agile might say, “User Stories!” as the answer to this problem. No, User Stories aren’t the magic bullet here. The solution is simply that developers and stakeholders have to have frequent conversations, so that they build the system together. Stakeholders will talk about the needs of their different users (User Stories), and the developers suggest solutions to address those needs. If the User Stories are just documents prepared and passed around, instead of being conversations, then they are little better than traditional requirements documentation.

Ok, so where does the documentation come in here? After having the conversation, the stakeholders and developers agree on a solution to each user need (User Story). But it doesn’t stop there – stakeholders and developers then agree on acceptance criteria, or even better, acceptance tests.

Acceptance criteria & acceptance test form the core of Agile requirements. Acceptance criteria and acceptance tests reduce the ambiguity around the requirement, improving the chances that developers build the right thing, that stakeholders will be happy with. It gives the developers flexibility in how they implement the requirements, as long as they meet the criteria/tests.

Furthermore, it teases out varying interpretations of the requirement among the stakeholders themselves – Often when we get to the acceptance criteria/test conversation, that’s when the stakeholders realize that each of them has a very different view of the requirement, and it gives them a chance to agree among themselves on the requirement before they have the team go and build it.

The criteria/tests become the common language between the developers and the stakeholders. Criteria and tests become the basis for discussing changes in requirements, as well as how progress is tracked. Furthermore, these tests can be automated, using Acceptance-Test Driven Development (ATDD) tools (Concordion, Robot Framework, Fitnesse… be sure to minimize the use of UI-testing for ATDD testing, rather run ATDD tests on the Service Layer).

In summary, the documentation of an Agile requirement is, at it’s core, acceptance criteria & acceptance tests, derived from conversations between stakeholders & developers. This is, of course, done iteratively – only a few requirements at a time, so that stakeholders can periodically see and use what’s being built before adding more requirements.

Technical Documentation

Probably an even bigger waste of time & effort, in many cases, is technical documentation. Technical documentation is meant to allow a system to be maintained by future developers, even when the original team has left. Very often, however, technical documentation, such as UML diagrams, are not very helpful in solving day-to-day development problems, and are often out-of-sync with the actual behavior of the system.

The best documentation for technical aspects are still tests, particularly automated tests. Automated tests are able to validate if the behavior specified is actually being implemented in the code, something that documentation on paper cannot do.

Since tests are documentation, it’s important for the members of the development team to write their tests in readable and expressive ways, being conscious that the tests are meant to be read by others as living documentation.

Unit Tests & Integration Tests

The root and core of Agile testing is unit testing, via Test-Driven Development (TDD). TDD means that before a programmer writes a method or updates a method’s behavior, the programmer must write an automated test that specifies the method’s behavior. This is a very deliberate way of programming that produces a lot of fine-grained documentation on the behavior of each component, if done properly.

When a new programmer joins the team, he/she can get productive very quickly, since examples of the usage and behavior of the methods are in the tests. And (if) when the new programmer introduces bugs, the tests not only catch the bugs, but (if well-written) provide helpful messages on what went wrong and what the proper behavior should be.

A level up from unit tests are integration tests. They are similar to unit tests only they test the behavior of more than one component at a time, usually including external systems such as databases, application containers or web resources. Integration tests, when done well, yield similar rich documentation on the behavior of the components.

Acceptance Tests: Automated Requirements

The drawback of unit tests and integration tests is that they are only appreciated by technical people, and not by business stakeholders. This misses out on the valuable feedback that the stakeholders can provide, which can help avoid wasted effort by developers in building the wrong requirements. User involvement, after all, has always been noted as the number one factor in the success or failure of a project, according to surveys.

A great way to get stakeholders involved in the project is the practice of Acceptance Test-Driven Development (ATDD). Test cases are written in ways that are easily readable and appreciated by business stakeholders. Tools are then used to connect the test cases to the system, and the test cases are annotated with weather they succeed or fail. ATDD allows stakeholders to participate in defining the behavior of the system, as well as helping them track the progress of the project.

When the team starts work on a Story or feature, the testers and developers can get together first to define and automate the acceptance tests. This helps maintain the focus of the team as they implement the Story or feature – the team focuses on the things that contribute to the acceptance criteria that the stakeholders what to see, and avoid being distracted by things that don’t.

When doing ATDD, it’s important to limit the tests to what the stakeholders want to see, and to write the tests in a way that can be appreciated by them. Tests that are too technical or overly repetitive or mundane should not be included. Those aspects should still be tested, but in other ways. The point of ATDD is involvement of the stakeholder.

I would again like to reiterate that majority of ATDD tests should be run against the Service Layer and not the UI. UI tests are fragile, and so incur a high cost of maintaining them with every little change in the system. Many attempts at automated testing fail because of the focus on UI test automation.

Other Tests

Many other aspects of the system can be documented through other forms of tests. Performance constraints can be written as automated tests using tools like JMeter or Load Runner. Behavior of the UI (in isolation of the rest of the system) may also be documented via automated or manual tests.

Not all tests need to be automated. Some tests are more economically run manually.

| Reference: | Agile Myth #7: “Agile Means No Documentation” from our JCG partner Calen Legaspi at the Calen Legaspi blog. |