Performance Tuning of an Apache Kafka/Spark Streaming System

Real-world case study in the telecom industry

Debugging a real-life distributed application can be a pretty daunting task. Most common Google searches don’t turn out to be very useful, at least at first. In this blog post, I will give a fairly detailed account of how we managed to accelerate by almost 10x an Apache Kafka/Spark Streaming/Apache Ignite application and turn a development prototype into a useful, stable streaming application that eventually exceeded the performance goals set for the application.

The lessons learned here are fairly general and extend easily to similar systems using MapR Streams as well as Kafka.

This project serves as a concrete case for the need of a converged platform, which integrates the full software stack to support the requirements of this system: real-time streams and big data distributed processing and persistence. The MapR Converged Data Platform is the only currently available production-ready implementation of such a platform as of this writing.

Goal of the system

To meet the needs of the telecom company, the goal of the application is to join together the log data from three separate systems. When the data is joined, it becomes possible to correlate the network conditions to a particular call for any particular customer, thus allowing customer support to provide accurate and useful information to customers who are unsatisfied with their phone service. The application has great additional value if it can do this work in real time rather than as a batch job, since call quality information that is 6 hours old has no real value for customer service or network operations.

Basically, this is a fairly straight-up ETL job that would normally be done as a batch job for a data warehouse but now has to be done in real time as a streaming distributed architecture.

More concretely, the overall picture is to stream the input data from a remote server into a distributed cluster, do some data cleaning and augmentation, join the records from the three logs, and persist the joined data as a single table into a database.

The problems with the original system

The original system had several issues centered around performance and stability.

First, the streaming application was not stable. In a Spark Streaming application, the stream is said to be stable if the processing time of each microbatch is equal to or less than the batch time. In this case, the streaming part of the application was receiving data in 30 second windows but was taking between 4.5-6 minutes to process.

Second, there is a batch process to join data one hour at a time that was targeted to run in 30 minutes but was taking over 2 hours to complete.

Third, the application was randomly crashing after running for a few hours.

The cluster hardware, software stack, and input data

The cluster hardware is pretty good, with 12 nodes of enterprise servers, each equipped with two E5 Xeon CPUs each with 16 physical cores, 256GB memory, and eight 6TB spinning HDD. The network is 10GB Ethernet.

The technology stack selected for this project is centered around Kafka 0.8 for streaming the data into the system, Apache Spark 1.6 for the ETL operations (essentially a bit of filter and transformation of the input, then a join), and the use of Apache Ignite 1.6 as an in-memory shared cache to make it easy to connect the streaming input part of the application with joining the data. Apache Hive is also used to serve as a disk backup for Ignite in case of failure and for separate analytics application.

The initial cluster was configured as follows:

| Node | Zk | NN | HDFS | Mesos | Mesos Master | Kafka | Spark Worker | Ignite |

| 1 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| 2 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| 3 | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| … | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| 7 | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| 8 | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| … | x | x | x | x | ||||

| 12 | x | x | x | x |

The cluster is running Apache Hadoop’s HDFS as a distributed storage layer, with resources managed by Mesos 0.28. Finally, HBase is used as the ultimate data store for the final joined data. It will be queried by other systems outside the scope of this project.

The performance requirement of the system is to handle an input throughput of up to 3GB/min, or 150-200,000 events/second, representing the known peak data throughput, plus an additional margin. The ordinary throughput is about half of that value or 1.5GB/min and 60,000-80,000 events/second.

The raw data source are the logs of three remote systems, labeled A, B, and C here: Log A comprises about 84-85% of the entries, Log B about 1-2%, and Log C about 14-15%. The fact that the data is unbalanced is one of the (many) sources of difficulty in this application.

The Spark applications are both coded in Scala 2.10 and Kafka’s direct approach (no receivers). Apache Ignite has a really nice Scala API with a magic IgniteRDD that can allow applications to share in-memory data, a key feature for this system to reduce coding complexity.

The application architecture

The raw data is ingested into the system by a single Kafka producer into Kafka running on 6 servers. The producer reads the various logs and adds each log’s records into its own topic. As there are three logs, there are three Kafka topics. Each topic is split into 36 partitions. Most likely, there are 36 partitions because there are 6 nodes with each 6 disks assigned to HDFS, and Kafka documentation seems to recommend having about one partition per physical disk as a guideline.

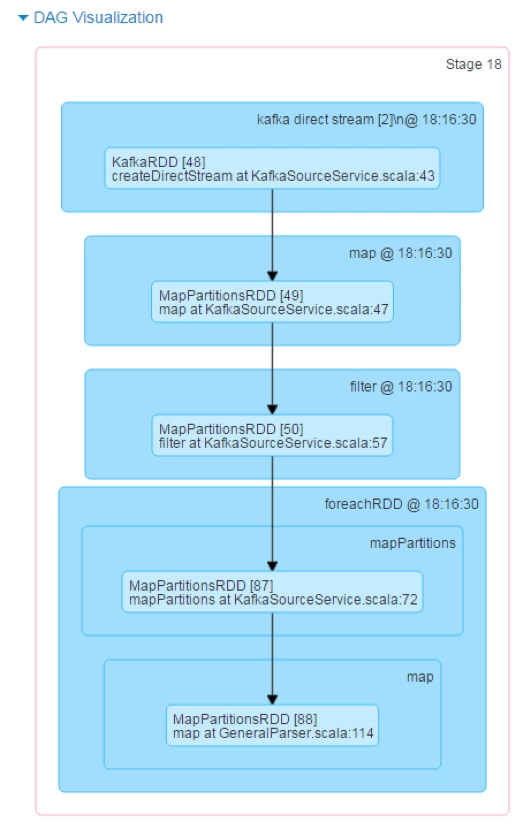

The data is consumed by a Spark Streaming application which picks up each topic and then does a simple filter to cut out unnecessary fields, a map operation to transform the data, and a foreachRDD operation (each micro-batch generates an RDD in Spark Streaming) that saves the data to Ignite and to Hive.

The streaming app is very straightforward: map, filter, and foreach partition to save to Ignite

A second “regular” Spark application runs on the data stored in-memory by Ignite to join the records from the three separate logs into a single table in batches of 1 hour. This job is done using Spark’s DataFrame API, which is ideally suited to the task. The second part involves no more than 100GB worth of data, and the cluster hardware is properly sized to handle that amount of data.

Three hours of data are accumulated into Ignite, because the vast majority of calls last for less than an hour, and we want to run the join on one hour’s worth of data at a time. Since some calls will start in one batch and finish in another, the system keeps three hours and only processes the middle one-hour batch, thus the join can succeed on close to 100% of the records.

It’s worth noting that a better all-streaming architecture could have avoided the whole issue with the intermediate representation in the first place. An illustrative, real-world case, built with more time and thought up-front, can end the entire project faster, as opposed to rushing headlong into coding the first working solution that comes to mind.

Performance tuning

The main issues for these applications were caused by trying to run a development system’s code, tested on AWS instances on a physical, on-premise cluster running on real data. The original developer was never given access to the production cluster or the real data.

Apache Ignite was a huge source of problems, principally because it is such a new project that nobody had any real experience with it and also because it is not a very mature project yet.

First target: Improve Spark Streaming performance

The Spark Streaming application was running in about 4.5 minutes, and the project goal was to run in about 30 seconds. We needed to find 9x speedup worth of improvements, and due to time constraints, we couldn’t afford to change any code!

The system had to be ready for production testing within a week, so the code from the architecture and algorithm point of view was assumed to be correct and good enough that we could reach the performance requirement only with tuning.

Fix RPC timeout exceptions

We found the correct solution from somebody having the same problem, as seen in SPARK-14140 in JIRA. They recommend increasing the spark.executor.heartbeatInterval from 10s to 20s.

I think this problem may be caused by nodes getting busy from disk or CPU spikes because of Kafka, Ignite, or garbage collector pauses. Since Spark runs on all nodes, the issue was random. (See the cluster services layout table in the first section.)

The configuration change fixed this issue completely. We haven’t seen it happen since.

Increase driver and executor memory

Out of memory issues and random crashes of the application were solved by increasing the memory from 20g per executor to 40g per executor as well as 40g for the driver. Happily, the machines in the production cluster were heavily provisioned with memory. This is a good practice with a new application, since you don’t know how much you will need at first.

The issue was difficult to debug with precision, lacking accurate information, since the Spark UI reports very little memory consumption. In practice, as this setting is easy to change, we empirically settled on 40g being the smallest memory size for the application to run stably.

Increase parallelism: increase number of partitions in Kafka

The input data was unbalanced, and most of the application processing time was spent processing Topic 1 (with 85% of the throughput). Kafka partitions are matched 1:1 with the number of partitions in the input RDD, leading to only 36 partitions, meaning we can only keep 36 cores busy on this task. To increase the parallelism, we need to increase the number of partitions. So we split topic 1 into 12 topics each, with 6 partitions, for a total of 72 partitions. We did a simple modification to the producer to divide the data evenly from the first log into 12 topics, instead of just one. Zero code needed to be modified on the consumer side.

We also right-sized the number of partitions for the two other topics, in proportion to their relative importance in the input data, so we set topic 2 to 2 partitions and topic 3 to 8 partitions.

Running more tasks in parallel. Before tuning, each stage always had 36 partitions!

Right-size the executors

The original application was running only 3 executors with 72 total cores. We configured the application to run with 80 cores at a maximum of 10 cores per executor, for a total of 8 executors. Note that with 16 real cores per node on a 10-node cluster, we’re leaving plenty of resources for Kafka brokers, Ignite, and HDFS/NN to run on.

Increase the batch window from 30s to 1m

The data is pushed into Kafka by the producer as batches every 30s, as it is gathered by FTP batches from the remote systems. Such an arrangement is common in telecom applications due to a need to deal with equipment and systems from a bewildering range of manufacturers, technology, and ages.

This meant that the input stream was very lumpy, as shown in the screenshot of Spark UI’s Streaming tab:

Increasing the window to 1m allowed us to smooth out the input and gave the system a chance to process the data in 1 minute or less and still be stable.

To make sure of it, the team generated a test data, which simulated the known worst-case data, and with the new settings, the spark-streaming job was now indeed stable. The team was also able to switch easily between test data and the real production data stream as well as a throttle on the producers to configure how much data to let in to the system. This was extremely helpful to test various configurations quickly and see if we had made progress or not.

Drop requirement to save to Hive, only use Ignite

Discussion with the project managers revealed that Hive was not actually part of the requirements for the streaming application! Mainly, this is because the data in HBase could just as easily be used by the analytics; also, in the context of this application, each individual record doesn’t actually need to be processed with a 100% guarantee.

Indeed, in light of the goal of the system, the worse-case scenario for missing data is that a customer’s call quality information cannot be found… which is already the case. In other words, the risk of data loss is not a deal-breaker, and the upside to gaining data is additional insights. As long as the great majority of the data is processed and stored, the business goals can be reached.

Results of all optimizations

The streaming application finally became stable, with an optimized runtime of 30-35s.

As it turns out, cutting out Hive also sped up the second Spark application that joins the data together, so that it now ran in 35m, which meant that both applications were now well within the project requirements.

With improvements from the next part, the final performance of the Spark Streaming job went down in the low 20s range, for a final speedup of a bit over 12 times.

Second target: Improve System Stability

We had to work quite hard on stability. Several strategies were required, as we will explain below.

Make the Spark Streaming application stable

The work we did to fix the performance had a direct impact on system stability. If both applications are stable themselves and running on right-sized resources, then the system has the best chance to be stable overall.

Remove Mesos and use Spark Standalone

The initial choice of Mesos to manage resources was forward-looking, but ultimately we decided to drop it from the final production system. At the onset, the plan was to have Mesos manage all the applications. But the team never could get Kafka and Ignite to play nice with Mesos, and so they were running in standalone mode, leaving only Spark to be managed by Mesos. Surely, with more time, there is little doubt all applications could be properly configured to work with Mesos.

Proposing to remove Mesos was a bit controversial, as Mesos is much more advanced and cool than Spark running in standalone mode.

But the issue with Mesos was twofold:

- Control over executor size and number was poor, a known issue (SPARK-5095) with Spark 1.6 and fixed in Spark 2.0.

- Ignite and Kafka weren’t running inside Mesos, just Spark. Because of schedule pressure, the team had given up on trying to get those two services running in Mesos.

Mesos can only ever allocate resources well if it actually controls resources. In the case of this system, Kafka and Ignite are running outside of Mesos’ knowledge, meaning it’s going to assign resources to the Spark applications incorrectly.

In addition, it’s a single-purpose cluster, so we can live with customizing the sizing of the resources for each application with a global view of the system’s resources. There is little need for dynamic resource allocations, scheduling queues, multi-tenancy, and other buzzwords.

Change the Ignite memory model

It is a known issue that when the heap controlled by the JVM gets very big (>32GB), the cost of garbage collection is quite large. We could indeed see this problem when the join application runs: the stages with 25GB shuffle had some rows with spikes in GC time, ranging from 10 seconds up to more than a minute.

The initial configuration of Ignite was to run ONHEAP_TIERED with 48GB worth of data cached on heap, then overflow drops to 12GB of off-heap memory. That setting was changed to the OFFHEAP_TIERED model. While slightly slower due to serialization cost, OFFHEAP_TIERED doesn’t result in big garbage collections. It still runs in memory, so we estimated it would be a net gain.

With this change, the run time for each batch dutifully came down by about five seconds, from 30 seconds down to about 25 seconds. In addition, successive batches tended to have much more similar processing time with a delta of 1-3 seconds, whereas it would previously vary by over 5 to 10 seconds.

Update the Ignite JVM settings

We followed the recommended JVM options as found in Ignite documentation’s performance tuning section (http://apacheignite.gridgain.org/docs/jvm-and-system-tuning).

Improve the Spark code

Some parts of the code assumed reliability, like queries to Ignite, when in fact there was a possibility of the operations failing. These problems can be fixed in the code, which now handles exceptions more gracefully, though there is probably work left to increase the robustness of the code. We can only find these spots by letting the application run now.

Reassign ZooKeeper to nodes 10-12

Given that the cluster is medium-sized, it’s worth spreading the services as much as possible. We moved the ZooKeeper services from nodes 1-3 to nodes 10-12.

Conclusion

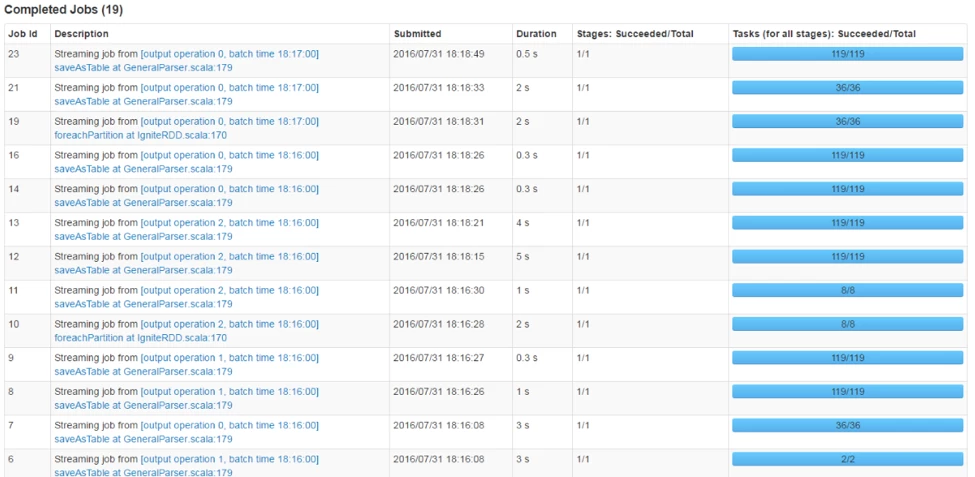

Tuning this application took about 1 week of full-time work. The main information we used was Spark UI and Spark logs, easily accessible from the Spark UI. The view of Jobs and Stages as well as the streaming UI are really very useful.

What I learned

- Migrating a streaming application from a prototype on AWS to an on-premise cluster requires schedule time for testing

- Not testing the AWS prototype with realistic data was a big mistake

- Including many “bleeding-edge” OSS components (Apache Ignite and Mesos) with expectations of very high reliability is unrealistic

- A better architecture design could have simplified the system tremendously

- Tuning a Kafka/Spark Streaming application requires a holistic understanding of the entire system. It’s not simply about changing the parameter values of Spark; it’s a combination of the data flow characteristics, the application goals and value to the customer, the hardware and services, the application code, and then playing with Spark parameters.

- MapR Converged Data Platform would have cut the development time, complexity, and cost for this project.

The project is a first for this particular telecom company, and they decided to go all-out on such an advanced, 100% open-source platform. They should be applauded for their pioneering spirit. But a better choice of platform and application architecture would have made their lives a lot easier.

The need for a converged big-data platform is now

In fact, the requirements for this project show the real-world business need for a state-of-the-art converged platform with a fast distributed files system, high-performance key-value store for persistence, and real-time streaming capabilities.

A MapR solution could probably skip the requirement for a still speculative open-source project like Ignite, since the full software stack required by the architecture is already built-in and fully supported. Given this system is heading into production for a telecom operator with 24/7 reliability expectation, such an advantage is considerable.

| Reference: | Performance Tuning of an Apache Kafka/Spark Streaming System from our JCG partner Mathieu Dumoulin at the Mapr blog. |