Should we always use TDD to design?

Can design emerge from TDD? Should we always use TDD to design software? Should we design upfront? How much design should we do and when?

Those are common questions that often generate a lot of debate. People involved in those debates often have very different definitions of design and also the scope where it happens. It is difficult to have a sensible discussion without first agreeing on some definitions.

Software Design Definition

Let’s check what Wikipedia says:

Software design is the process by which an agent creates a specification of a software artefact, intended to accomplish goals, using a set of primitive components and subject to constraints. Software design may refer to either “all the activity involved in conceptualizing, framing, implementing, commissioning, and ultimately modifying complex systems” or “the activity following requirements specification and before programming, as … [in] a stylized software engineering process.” – Wikipedia.

I find this definition a bit cumbersome and somehow makes me think about the Waterfall process, with a big design phase before any code is implemented.

A quick Google can show us many other definitions and most of them say similar things but in different ways. For the sake of brevity, I won’t add them all here. I’ll use my own definition:

Software Design is the continuous process of specifying software modules responsible for providing well-defined and cohesive behaviour in a way they can be easily understood, combined, changed and replaced over time.

The problem with this definition is that it does not only define software design but it also makes a reference to a way of working, that means, it implies that design should be done incrementally as part of the development process and not fully up-front. For those who do not like that way of working, we can leave that as an optional part of the description for now.

Software Design is the [continuous] process of specifying software modules responsible for providing well-defined and cohesive behaviour in a way they can be easily understood, combined, changed and replaced [over time].

Software Design levels and impacts

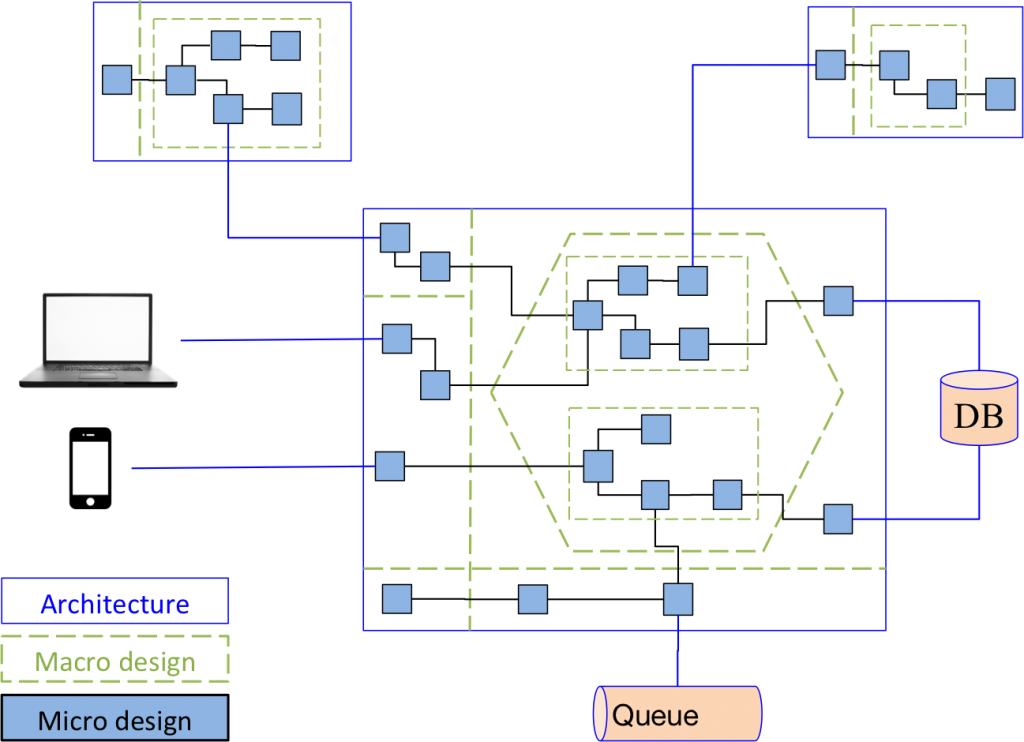

Software design happens at many different levels and not all design techniques are suitable for every level. Although systems can present multiple levels of details, I’ll simplify the different levels where design can happen for sake of simplicity.

Architecture: Design at this level is the process of defining the responsibility of different systems and how they will interact with each other. Here we also might define technology stack, persistence mechanisms, general strategies for security, performance, logging, monitoring, and deployment. Bad decisions or changes at this level can significantly impact the whole project.

Macro design: Design at this level is the process of defining the general structure of a single system. This structure can be related to layers, separation of delivery mechanism from core domain, hexagonal architecture, components, layers of indirection, high level abstractions, packages/namespaces. We might also define the technology stack and some of the architectural concerns described above but for a single system only. Decisions at this level should impact the system itself, not the rest of the ecosystem.

Micro design: Design at this level is the process of defining the details at code level, focusing on the internals of high level concepts defined at the macro level. Design at micro level means defining classes, methods, functions, parameters, return types, and a few small components. Decisions at this level tend to have very little impact at the system level and no impact at architectural level.

Design approaches

Besides the different levels where design happens, there’s also different ways of making design decisions. They are mostly related to when we make these decisions.

Big Design Up Front (BDUF): Usually associated to the waterfall process, BDUF is the process of designing a whole system up front (before development), and it can range from high level concepts (architecture, services, protocols, database) to low level concepts (classes, methods).

Strategic Design: The process of defining the main parts of the ecosystem and its overall architecture. Differently from BDUF, Strategic Design does not go into the detail. Its purpose is to provide a technical vision based on the most important business requirements. This high-level vision describes services, their responsibilities, the way they communicate, architectural components, main business flows, persistence, APIs, etc.

Just-in-Time Design: The process of defining software modules at the moment they are about to be built. This design process can be used at macro or micro design. Just-in-Time design is quite common in Outside-In TDD (London School), where collaboration among modules are defined during TDD’s Red phase. The Refactoring phase is normally about minor design refinements when using Outside-In TDD.

Emergent Design: The process of defining software modules based on code that has just been written. This design process is often applied at a micro design level and gradually pushed up to macro design. Emergent Design is commonly found in Classicist TDD (Chicago School), where design is done during TDD’s Refactoring phase, as a way to improve existing working code written in the Green phase.

Complexity levels

Complexity is another perspective that needs to be taken into account when deciding on a design strategy. Complexity can take many forms and is out of the scope of this article to describe all types of complexity we can find in a software project. But for the sake of brevity, let’s consider complex anything we cannot immediately understand or visualise a solution for. Complexity can be present at any level – architecture, macro or micro design. Different design approaches should be used according to the degree of complexity and the level it occurs.

TDD can generally be used at micro level to resolve complex problems in a step-by-step manner, mainly when inputs, outputs and/or side effects are known. An example would be algorithms like the Roman Numeral kata or calculating an insurance premium. However, some problems at micro level would certainly benefit from some up-front thinking, like implementing a genetic algorithm.

Design discovery process

The design discovery process should vary not only across different levels but also according to our familiarity with the problem domain. We should be able to design a familiar problem straightaway, regardless if we are at an architectural or micro design level. In cases like that, there are not many advantages to design up-front. I would rather do it design incrementally, while writing the code. But not always we are familiar with the problem domain and in order to minimise risk, we should do some up-front investigation, creating prototypes, running workshops with business people or other teams, and draw a few things on a white board.

Last Responsible Moment vs Cost of Delay

We will always know more tomorrow than we know today. Making important decisions too early, when we know the least about a project, can seriously damage the project for a long time. I remember when the architecture group of an investment bank decided very early on that our team had to use a data grid in one of our new projects. That decision was extremely harmful for the project and painful for us developers, as we discovered during the first months of development that we could build the same system in a much simpler and faster way. But at that point it was too late to change.

A very sensible advice is to make architectural decisions at the last responsible moment. There is that famous story of a team that delayed their decision on what database to use and built the core of their system using an in-memory repository. When they were happy with the features, they realised that they could store everything in files instead of using a database, making their system much simpler to deploy and use. This is great, but it is just one side of the story. The other side is that they took one year to go live since their system could not persist data. Delaying the decision on their persistence mechanism was also delayed their go live date.

Delaying design decisions often implies an increasing cost of delay. Instead of delaying an architecture decision, we should focus on reducing the cost of changing the decision, designing our architecture in a way that the coupling between architectural components are minimised.

Enabling parallel work

When working as part of a single team, we can easily agree when to make design decisions as no one else is impacted. However, in environments where multiple teams collaborate, some design up-front is needed to enable teams to work in parallel without many disruptions. Integrating the work of multiple teams is also easier when they work behind well-defined interfaces or APIs.

Parallel and incremental design at all levels

Continuous deployment is a goal for many companies and for that we need to develop features in vertical slices and continuously evolve all parts of our design, from the architecture to micro design. The difference across levels is normally the rate of change. At architecture level, we would define the bare minimum necessary to support the most important features (let’s say, features which would be part of a Minimum Viable Product (MVP) or milestone). This way the architecture would evolve every few months, the macro design every month or so, and micro design on a daily basis.

Size of design and test steps

The line between macro and micro design can be a bit blurred sometimes. Often, I need to decide between using Just-In-Time Design and Emergent Design. The decision is related to the level of confidence I have. The more confident I am with the solution I want to give to a problem, the larger my TDD steps will be. In this case, Outside-In TDD, focusing on behaviour and collaboration while writing the tests is my preferred TDD style. However, there are times I cannot easily visualise a solution or I am not confident that the solution I have in my head is a good solution. In this case, I flip to Classicist TDD and use very small steps in my tests, making no design assumptions on the Red phase, going to Green as soon as possible with the simplest implementation I can find, and then use the Refactoring phase to decide if and how I want to improve the design. Four Rules of Simple Design and SOLID Principles are the design guidelines I use during the Refactoring phase.

Test-driving architecture

Some people say they test-drive architecture. That may be true, but I believe they actually use a Test First approach, and do not necessarily benefit from a quick sequence of short Red-Green-Refactoring iterations to evolve the architecture like we would have in TDD. In the Test First approach the test is there to make sure a specific functional or non-functional requirement is satisfied and not as an aid for discovering the architecture incrementally. TDDing architecture can be a big waste of time. I prefer to use the Double Loop of TDD, starting with an Acceptance Test to give me the direction and then use Unit Tests to grow the solution. I also like the idea of Architectural Fitness Functions – we had them at UBS to make sure throughput and latency were at acceptable levels – but they are not exactly TDD.

Is it OK to write tests afterwards?

In a few occasions I do it for architecture and black box tests as I prefer to wait for the interface and business features to stabilise. These tests are normally a pain to write and maintain (normally they have a complex setup), so I prefer to write them after I have a good idea of what I need to test and how to make it work.

Guidelines we generally follow

Due to the impact and complexity, we normally design architecture up-front, that means, before we write any test or code. How up-front varies from project to project. We favour incremental architecture and normally use features of the next milestone as the basis of our architectural decisions. We accept the risk things might change in the following milestone but trying to reduce this risk has proven to be quite wasteful.

At a macro design level, we normally do some quick white board sessions and discuss the main components of the application. We also agree if we are going to use layers, hexagonal architecture, and how the delivery mechanism and infrastructure will be decoupled from the core domain. Due to our familiarity with the macro design decisions and our preference for developing code in small vertical slices, Outside-In TDD is our favourite approach.

At micro level, the vast majority of our design decisions come from TDD, using a combination of Outside-In and Classicist TDD. Although coming from outside, we often use small steps and triangulation in parts of the flow to flush out algorithms, details of components, and even some infrastructure code.

Conclusion

For me the question is not IF we should or should not design up front, but WHEN. Design happens at many different levels (architecture, macro and micro) and have different degrees of complexity. We also need to understand who the consumers of the design are.

There are different design styles and techniques, from BDUF to Classicist TDD. I’m not a big fan of extremes so I prefer to be somewhere in between, sometimes using Emergent Design but rarely BDUF.

Be pragmatic. Do not follow practices blindly. Sometimes a couple of hours drawing on a white board can save a couple of months’ worth of work.

| Published on Java Code Geeks with permission by Sandro Mancuso, partner at our JCG program. See the original article here: Should we always use TDD to design? Opinions expressed by Java Code Geeks contributors are their own. |

Software engineering is the most abstract of engineering disciplines in that it does not produce solid, concrete results (try weighing software sometimes). This means correctness and the proof of correctness of software is also the most abstract of the various engineering disciplines. That puts a special impetus to the software design phase that differs from the design phase of, say, electronics engineering. Software design is actually not a single phase or event (despite things like waterfall processes hope to the contrary). Instead, it is a continuous effort of converting requirements into implemented code. Depending on the complexity, size, scope, and… Read more »