Java: Chronicle Bytes, Kicking the Tires

Reading and writing binary data with Java can sometimes be a hassle. Read this article and learn how to leverage Chronicle Bytes, thereby making these tasks both faster and easier.

I recently contributed to the open-source project “Chronicle Decentred” which is a high-performance decentralized ledger based on blockchain technology. For our binary access, we relied on a library called “Chronicle Bytes” which caught my attention. In this article, I will share some of the learnings I made while using the Bytes library.

What is Bytes?

Bytes is a library that provides functionality similar to Java’s built-inByteBuffer but obviously with some extensions. Both provide a basic abstraction of a buffer storing bytes with additional features over working with raw arrays of bytes. They are also both a VIEW of underlying bytes and can be backed by a raw array of bytes but also native memory (off-heap) or perhaps even a file.

Here is a short example of how to use Bytes:

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 | // Allocate off-heap memory that can be expanded on demand.Bytes bytes = Bytes.allocateElasticDirect();// Write databytes.writeBoolean(true) .writeByte((byte) 1) .writeInt(2) .writeLong(3L) .writeDouble(3.14) .writeUtf8("Foo") .writeUnsignedByte(255);System.out.println("Wrote " + bytes.writePosition() + " bytes");System.out.println(bytes.toHexString()); |

Running the code above will produce the following output:

1 2 3 | Wrote 27 bytes00000000 59 01 02 00 00 00 03 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 1f 85 Y······· ········00000010 eb 51 b8 1e 09 40 03 46 6f 6f ff ·Q···@·F oo· |

We can also read back data as shown hereunder:

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 | // Read databoolean flag = bytes.readBoolean();byte b = bytes.readByte();int i = bytes.readInt();long l = bytes.readLong();double d = bytes.readDouble();String s = bytes.readUtf8();int ub = bytes.readUnsignedByte();System.out.println("d = " + d);bytes.release(); |

This will produce the following output:

1 | d = 3.14 |

HexDumpBytes

Bytes also provides a HexDumpBytes which makes it easier to document your protocol.

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 | // Allocate off-heap memory that can be expanded on demand.Bytes bytes = new HexDumpBytes();// Write databytes.comment("flag").writeBoolean(true) .comment("u8").writeByte((byte) 1) .comment("s32").writeInt(2) .comment("s64").writeLong(3L) .comment("f64").writeDouble(3.14) .comment("text").writeUtf8("Foo") .comment("u8").writeUnsignedByte(255);System.out.println(bytes.toHexString()); |

This will produce the following output:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | 59 # flag01 # u802 00 00 00 # s3203 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 # s641f 85 eb 51 b8 1e 09 40 # f6403 46 6f 6f # textff # u8 |

Summary

As can be seen, it is easy to write and read various data formats and Bytes maintain separate write and read positions making it even easier to use (No need for “flipping” aBuffer). The examples above illustrate “streaming operations” where consecutive write/reads are made. There are also “absolute operations” that provide us with random access within the Bytes’ memory region.

Another useful feature of Bytes is that it can be “elastic” in the sense that its backing memory is expanded dynamically and automatically if we write more data than we initially allocated. This is similar to anArrayList with an initial size that is expanded as we add additional elements.

Comparison

Here is a short table of some of the properties that distinguishBytes from ByteBuffer:

| ByteBuffer | Bytes | |

| Max size [bytes] | 2^31 | 2^63 |

| Separate read and write position | No | Yes |

| Elastic Buffers | No | Yes |

| Atomic operations (CAS) | No | Yes |

| Deterministic resource release | Internal API (Cleaner) | Yes |

| Ability to bypass initial zero-out | No | Yes |

| Read/Write strings | No | Yes |

| Endianness | Big and Little | Native only |

| Stop Bit compression | No | Yes |

| Serialize objects | No | Yes |

| Support RPC serialization | No | Yes |

How Do I Install it?

When we want to use Bytes in our project, we just add the following Maven dependency in our pom.xml file and we have access to the library.

1 2 3 4 5 | <dependency> <groupId>net.openhft</groupId> <artifactId>chronicle-bytes</artifactId> <version>2.17.27</version></dependency> |

If you are using another build tool, for example, Gradle, you can see how to depend on Bytes by clicking this link.

Obtaining Bytes Objects

A Bytes object can be obtained in many ways, including wrapping an existing ByteBuffer. Here are some examples:

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 | // Allocate Bytes using off-heap direct memory// whereby the capacity is fixed (not elastic)Bytes bytes = Bytes.allocateDirect(8);// Allocate a ByteBuffer somehow, e.g. by calling// ByteBuffer's static methods or by mapping a fileByteBuffer bb = ByteBuffer.allocate(16);//// Create Bytes using the provided ByteBuffer// as backing memory with a fixed capacity.Bytes bytes = Bytes.wrapForWrite(bb);// Create a byte arraybyte[] ba = new byte[16];//// Create Bytes using the provided byte array// as backing memory with fixed capacity.Bytes bytes = Bytes.wrapForWrite(ba);// Allocate Bytes which wraps an on-heap ByteBufferBytes bytes = Bytes.elasticHeapByteBuffer(8);// Acquire the current underlying ByteBufferByteBuffer bb = bytes.underlyingObject();// Allocate Bytes which wraps an off-heap direct ByteBufferBytes bytes = Bytes.elasticByteBuffer(8);// Acquire the current underlying ByteBufferByteBuffer bb = bytes.underlyingObject();// Allocate Bytes using off-heap direct memoryBytes bytes = Bytes.allocateElasticDirect(8);// Acquire the address of the first byte in underlying memory// (expert use only)long address = bytes.addressForRead(0);// Allocate Bytes using off-heap direct memory// but only allocate underlying memory on demand.Bytes bytes = Bytes.allocateElasticDirect(); |

Releasing Bytes

With ByteBuffer, we normally do not have any control of when the underlying memory is actually released back to the operating system or heap. This can be problematic when we allocate large amounts of memory and where the actual ByteBuffer objects as such are not garbage collected.

This is how the problem may manifest itself: Even though theByteBuffer objects themselves are small, they may hold vast resources in underlying memory. It is only when the ByteBuffers are garbage collected that the underlying memory is returned. So we may end up in a situation where we have a small number of objects on the heap (say we have 10 ByteBuffers holding 1 GB each). The JVM finds no reason to run the garbage collector with only a few objects on heap. So we have plenty of heap memory but may run out of process memory anyhow.

Bytes provides a deterministic means of releasing the underlying resources promptly as illustrated in this example below:

1 2 3 4 5 6 | Bytes bytes = Bytes.allocateElasticDirect(8);try { doStuff(bytes);} finally { bytes.release();} |

This will ensure that underlying memory resources are released immediately after use.

If you forget to call release(), Bytes will still free the underlying resources when a garbage collection occurs just like ByteBuffer, but you could run out of memory waiting for that to happen.

Writing Data

Writing data can be made in two principal ways using either:

- Streaming operations

- Absolute operations

Streaming Operations

Streaming operations occur as a sequence of operations each laying out its contents successively in the underlying memory. This is much like a regular sequential file that grows from zero length and upwards as contents are written to the file.

1 2 3 4 | // Write in sequential orderbytes.writeBoolean(true) .writeByte((byte) 1) .writeInt(2) |

Absolute Operations

Absolute operations can access any portion of the underlying memory in a random access fashion much like a random access file where content can be written at any location at any time.

1 2 3 4 | // Write in any orderbytes.writeInt(2, 2) .writeBoolean(0, true) .writeByte(1, (byte) 1); |

Invoking absolute write operations does not affect the write position used for streaming operations.

Reading Data

Reading data can also be made using streaming or absolute operations.

Streaming Operations

Analog to writing, this is how streaming reading looks like:

1 2 3 | boolean flag = bytes.readBoolean();byte b = bytes.readByte();int i = bytes.readInt(); |

Absolute Operations

As with absolute writing, we can read from arbitrary positions:

1 2 3 | int i = bytes.readInt(2);boolean flag = bytes.readBoolean(0);byte b = bytes.readByte(1); |

Invoking absolute read operations does not affect the read position used for streaming operations.

Miscellaneous

Bytes supports writing of Strings which ByteBuffer does not:

1 | bytes.writeUtf8("The Rain in Spain stays mainly in the plain"); |

There are also methods for atomic operations:

1 | bytes.compareAndSwapInt(16, 0, 1); |

This will atomically set the int value at position 16 to 1 if and only if it is 0. This provides thread-safe constructs to be made using Bytes. ByteBuffer cannot provide such tools.

Benchmarking

How fast is Bytes? Well, as always, your mileage may vary depending on numerous factors. Let us compare ByteBuffer and Bytes where we allocate a memory region and perform some common operations on it and measure performance using JMH (initialization code not shown for brevity):

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 | @Benchmarkpublic void serializeByteBuffer() { byteBuffer.position(0); byteBuffer.putInt(POINT.x()).putInt(POINT.y());}@Benchmarkpublic void serializeBytes() { bytes.writePosition(0); bytes.writeInt(POINT.x()).writeInt(POINT.y());}@Benchmarkpublic boolean equalsByteBuffer() { return byteBuffer1.equals(byteBuffer2);}@Benchmarkpublic boolean equalsBytes() { return bytes1.equals(bytes2);} |

This produced the following output:

1 2 3 4 5 | Benchmark Mode Cnt Score Error UnitsBenchmarking.equalsByteBuffer thrpt 3 3838611.249 ± 11052050.262 ops/sBenchmarking.equalsBytes thrpt 3 13815958.787 ± 579940.844 ops/sBenchmarking.serializeByteBuffer thrpt 3 29278828.739 ± 11117877.437 ops/sBenchmarking.serializeBytes thrpt 3 42309429.465 ± 9784674.787 ops/s |

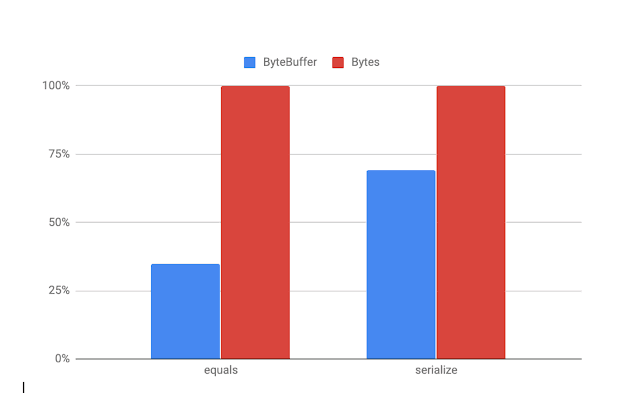

Here is a diagram of the different benchmarks showing relative performance (higher is better):

The performance Bytes is better than ByteBuffer for the benchmarks run.

Generally speaking, it makes sense to reuse direct off-heap buffers since they are relatively expensive to allocate. Reuse can be made in many ways including ThreadLocal variables and pooling. This is true for bothBytes and ByteBuffer.

The benchmarks were run on a Mac Book Pro (Mid 2015, 2.2 GHz Intel Core i7, 16 GB) and under Java 8 using all the available threads. It should be noted that you should run your own benchmarks if you want a relevant comparison pertaining to a specific problem.

APIs and Streaming RPC calls

It is easy to setup an entire framework with remote procedure calls (RPC) and APIs using Bytes which supports writing to and replaying of events. Here is a short example where MyPerson is a POJO that implements the interface BytesMarshable. We do not have to implement any of the methods in BytesMarshallable since it comes with default implementations.

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 | public final class MyPerson implements BytesMarshallable { private String name; private byte type; private double balance; public MyPerson(){} // Getters and setters not shown for brevity}interface MyApi { @MethodId(0x81L) void myPerson(MyPerson byteable);}static void serialize() { MyPerson myPerson = new MyPerson(); myPerson.setName("John"); yPerson.setType((byte) 7); myPerson.setBalance(123.5); HexDumpBytes bytes = new HexDumpBytes(); MyApi myApi = bytes.bytesMethodWriter(MyApi.class); myApi.myPerson(myPerson); System.out.println(bytes.toHexString());} |

Invoking serialize() will produce the following output:

1 2 3 4 | 81 01 # myPerson 04 4a 6f 68 6e # name 07 # type 00 00 00 00 00 e0 5e 40 # balance |

As can be seen, It is very easy to see how messages are composed.

File-backed Bytes

It is very uncomplicated to create file mapped bytes that grow as more data is appended as shown hereunder:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | try { MappedBytes mb = MappedBytes.mappedBytes(new File("mapped_file"), 1024); mb.appendUtf8("John") .append(4.3f);} catch (FileNotFoundException fnfe) { fnfe.printStackTrace();} |

This will create a memory mapped file named “mapped_file”.

1 2 3 4 5 | $ hexdump mapped_file 0000000 4a 6f 68 6e 34 2e 33 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 000000010 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00*0001400 |

Licensing and Dependencies

Bytes is open-source and licensed under the business-friendly Apache 2 license which makes it easy to include it in your own projects whether they are commercial or not.

Bytes have three runtime dependencies: chronicle-core, slf4j-api andcom.intellij:annotations which, in turn, are licensed under Apache 2, MIT and Apache 2.

Resources

Chronicle Bytes: https://github.com/OpenHFT/Chronicle-Bytes

The Bytes library provides many interesting features and provides good performance.

Published on Java Code Geeks with permission by Per Minborg, partner at our JCG program. See the original article here: Java: Chronicle Bytes, Kicking the Tires Opinions expressed by Java Code Geeks contributors are their own. |