Get Groovy with Gradle

Friends don’t let friends write user auth. Tired of managing your own users? Try Okta’s API and Java SDKs today. Authenticate, manage, and secure users in any application within minutes.

In the Java world, there are two main build systems: Gradle and Maven. A build system chiefly manages potentially complex webs of dependencies and compiles the project. It also packages the compiled project along with all the resources and meta files into the final .war or .jar file. For simple builds, the choice between Maven and Gradle is pretty much one of personal taste, or perhaps the taste of your CTO or technical manager. They both work great. However, for more complex projects, Gradle is a winner.

Pros and Cons of Building with Gradle

I personally love Gradle; I hate XML and spent several years working on a large, complex Java/Groovy project that would have been impossible without Gradle. Aside from the lack of XML, Gradle offers flexibility and build speed, using build files written in Groovy or Kotlin. With the full power of Kotlin or Groovy, along with the Gradle API libraries, you can create build scripts of staggering power and complexity. This can certainly be a blessing and a curse.

The DSL (domain-specific language) takes some getting used to, and Gradle has a reputation of being hard to learn; however, I think this is mostly because people are already accustomed to Maven. With Gradle, you essentially learn a build language, rather than just hacking away at XML. Using Gradle to its full potential certainly has a much higher learning curve than simply adding a dependency in Maven; but adding a dependency to a Gradle file isn’t really any harder than in Maven. It is much simpler to extend and customize a Gradle build than to write a Maven plugin and customize build steps.

Gradle also shortens build times considerably, especially in larger projects, because it does a great job of only reprocessing tasks and files that have changed. Further, it provides a build cache and a build daemon that make repeated builds more performant. Also, like Maven, it uses parallel threading for dependency resolution and the project build. Again, for a small, simple build, this performance increase is probably not significant. But for larger projects, it’s huge.

So, to summarize. Gradle is:

- Faster for large projects

- Infinitely customizable == steeper learning curve

- Uses Groovy or Kotlin instead of XML

While Maven is:

- Tried and true

- Ubiquitous

- Simpler for smaller projects that don’t require customization

- Plagued with XML and angle brackets

What’s Great about Groovy

Just a quick word about Groovy. Groovy is a JVM language, in that it compiles down to the same byte-code as Java and inter-operates seamlessly with Java classes. Groovy is a backwards compatible superset of Java, meaning that Groovy can transparently interface with Java libraries and code. However, it also adds a ton of new features: optional typing, functional programming, runtime flexibility, and lots of meta-programming stuff. It also greatly cleaned up a lot of Java’s wordy, ceremony code. Groovy hasn’t taken off as a mainstream development language, largely being overtaken by Scala and Kotlin, but it has found a niche in testing (because of its streamlined syntax and the meta-programming features) and in build systems.

Dependencies

You’ll need to install a few things for this tutorial (as well as sign up for an Okta account):

Java: you probably already have Java installed. This tutorial requires at least Java 1.8. If not, navigate to the OpenJDK website and install it. You could also install java using Homebrew on OSX and Linux using: brew cask install java.

Gradle: typically with a Gradle build you don’t actually have to install it. Gradle provides a feature called the Gradle wrapper that includes a script to download the correct Gradle version to build the project automatically. However, in this tutorial, since it’s a tutorial about Gradle, you might go ahead and install it. Just for fun. Gradle can be installed with homebrew, SDKMAN, or via download. They have instructions on the Gradle website.

Okta Developer Account: for the authentication portion of the sample application, you’ll need a free Okta developer account. You’ll be using Okta as an OAuth / OIDC (OpenID Connect) provider. If you don’t have one, please go to the Okta sign-up page and sign up. Note: The first time you log in, you’ll need to click the Admin button to get to the developer console.

HTTPie: You’re going to use a great command line utility to run a few HTTP requests from the command line. If you don’t already have it installed, head over to their website and install it.

Download the Sample Project

For the purposes of this tutorial, I’ve written a simple sample project. It’s a basic REST service written using Spring Boot and Java. Spring Boot makes it easy to build a secure Java web application. As an added bonus, I’ve included JWT authentication using OAuth 2.0 / OIDC (OpenID Connect). The authentication provider used by the project is Okta, a software-as-service identity management provider. You should have already signed up for a free developer account.

Please go ahead and download or clone the example project from the GitHub page and checkout the start branch.

git clone https://github.com/oktadeveloper/okta-spring-boot-gradle-example.git -b startcd reponame |

Get to Know build.gradle

The build.gradle file is the core of a Gradle project. It is where the build is configured. It’s equivalent to pom.xml for Maven (without all the horrible angle brackets – did I mention I was attacked by XML as a young developer and have never gotten over it?)

Let’s look at one. This comes from the example project that just downloaded.

// 1) configure the requirements to run the build scriptbuildscript { // set a custom property ext { springBootVersion = '2.1.6.RELEASE' } // check for dependencies in Maven Central when resolving the // dependencies in the buildscript block repositories { mavenCentral() } // we need the spring boot plugin to run the build script dependencies { classpath("org.springframework.boot:spring-boot-gradle-plugin:${springBootVersion}") } } // 2) apply some pluginsapply plugin: 'java' apply plugin: 'org.springframework.boot' apply plugin: 'io.spring.dependency-management' // 3) set some standard propertiesgroup = 'com.okta.springboottokenauth' version = '0.0.1-SNAPSHOT' sourceCompatibility = 1.8 // 4) repos to search to resolve dependencies for the projectrepositories { mavenCentral() } // 5) project dependenciesdependencies { implementation( 'com.okta.spring:okta-spring-boot-starter:1.2.1' ) implementation('org.springframework.boot:spring-boot-starter-security') implementation('org.springframework.boot:spring-boot-starter-web') testImplementation('org.springframework.boot:spring-boot-starter-test') testImplementation('org.springframework.security:spring-security-test') } |

The key to understanding a Gradle build file is to realize it’s a script, built in a Groovy DSL. Roughly speaking, it’s a configuration script that calls a series of closures (think functions, more in a bit on this) that define configuration options. It almost looks like JSON or a property file, and while that’s technically very wrong under the hood, it’s not that far off as a starting point.

However, the real power comes because build.gradle is a Groovy script. Thus it can execute arbitrary code and access any Java library, build-specific Gradle DSL and the Gradle API. You could probably launch the space shuttle with a Gradle file.

The Gradle buildscript

Let’s look at the script from the top down:

1) The buildscript closure configures the properties, dependencies, and source repositories required for the build script itself (as opposed to the application).

2) Next, apply plugin, shockingly, applies plugins. These extend the basic capability of the Gradle-Groovy DSL framework: the java plugin is applied, along with Spring Boot and Spring dependency management. The Java plugin configures Gradle to expect the standard Java project directory structure: src/main/java, src/main/resources, src/test/java, etc. These can be configured to change the default directories or adding new directories. The Gradle Java plugin docs are a good place to peruse more info.

3) Next, some standard properties are applied to the build.

4) The repositories block defines where the build script will look for dependencies. Maven Central is most common (mavenCentral()), but other repositories can be configured as well, including custom and local ones. A local Maven cache can be configured as a repository using mavenLocal(). This is helpful if a team wants to coordinate builds between projects but doesn’t want to actually tie the project build files together.

5) Finally, the project dependencies are defined.

The order of the standard, pre-defined closures doesn’t matter, since most build.gradle files only define dependencies, set project properties, and use predefined tasks, the order of the elements in the file doesn’t matter. There is no reason the repositories block has to go before the dependencies block, for example. You can think of the build.gradle file as simply a configuration file that Gradle reads before executing whatever tasks it was assigned by the shell command that called it.

It gets more complicated, however, when you start using the power of Gradle to define custom tasks and perform arbitrary code. Gradle will read the build.gradle file in a top-down manner, and execute any code blocks it finds therein; depending on what this code is doing, it could create an enforced ordering in the script. Further, when you define custom tasks and properties (not found in the Gradle API), ordering matters because these symbols will not be pre-defined and as such must be defined in the build script before you can use them.

What’s a Closure?

Back when Groovy first came out, functional programming was pretty niche and bringing things like closures into the JVM felt crazy. These days, it’s a lot more common: every function in Javascript is a closure. Generally speaking, a closure is a first-class function with a scope bound to it.

This means two things:

- Closures are functions that can be passed as variables at runtime

- Closures retain access to the variable scope where they are defined

The Java version of a closure is called a lambda. These were introduced into Java with version 1.8, not incidentally this happened around the same time Groovy was gaining initial popularity and functional programming was taking off.

To demonstrate a lambda, take a look at the JUnit test named LambdaTest.java.

src/test/java/com/okta/springboottokenauth/LambdaTest.java

interface SimpleLambda { public int sum(int x, int y); } public class LambdaTest { // create a lambda function with an var // encapsulated in its scope public SimpleLambda getTheLambda(int offset) { int scopedVar = offset; return (int x, int y) -> x + y + scopedVar; } @Test public void testClosure() { // get and test a lambda/closure with offset = 1 SimpleLambda lambda1 = getTheLambda(1); assertEquals(lambda1.sum(2,2), 5); // get and test a lambda/closure with offset = 2 SimpleLambda lambda2 = getTheLambda(2); assertEquals(lambda2.sum(2,2), 6); }} |

This example is a bit contrived, but demonstrates the two basic properties of lambdas. In the closure, or lambda function, implementation is defined in the getTheLambda(int offset) method. The lambda is created with the offset variable encapsulated in the closure scope and returned. This lambda is assigned to a variable. It can be called repeatedly, and it will reference the same scope. Further, a new lambda can be created with a new offset variable encapsulated in a separate scope and assigned to a different variable.

Coming from a strong object-oriented background, closures initially felt like wormholes being punched through the strict object-scope continuum, strangely connecting various parts of object over space and time.

Gradle is Nothing But Closures

Take the dependencies section of the build.gradle file:

dependencies { implementation( 'com.okta.spring:okta-spring-boot-starter:1.2.1' ) implementation('org.springframework.boot:spring-boot-starter-security') ...} |

Without the Groovy DSL shorthand, this is actually:

project.dependencies({ implementation( 'com.okta.spring:okta-spring-boot-starter:1.2.1' ) implementation('org.springframework.boot:spring-boot-starter-security') ... }) |

Everything in the brackets is actually a closure passed to the project.dependencies() method. The project object is an instance of the Project class, the main API parent class for the build.

As you can see, these functions pass in a series of dependencies as strings. So why not just use a more traditional static data structure like JSON, properties, or XML? Because these overloaded functions can accept closure code blocks as well, allowing for deep customization.

The definition of this block from the docs for the Project class on the Gradle website:

dependencies{ }

Configures the dependencies for this project.

This method executes the given closure against theDependencyHandlerfor this project. TheDependencyHandleris passed to the closure as the closure’s delegate.

We don’t need to get too deep into Groovy closures, but the delegate object mentioned above is an assignable context object. It’s used like the Javascript binding this , but here the delegate is a separate, assignable variable that leaves the actual execution scope untouched and accessible.

Exploring Gradle Dependency Configurations

Inside the dependency block are a sequence of configurations and names.

dependencies { configurationName dependencyNotation} |

Our build.gradle file uses two configurations: implementation and testImplementation.

implementation() defines a dependency required at compile time. This configuration method was called compile. testImplementation() and defined a dependency required for testing only (the old testCompile).

Another dependency configuration you’ll likely see is runtimeOnly and testRuntimeOnly. This declares dependencies provided at runtime that do not need to be compiled against.

There are more ways to define dependencies than is useful for the scope of this article. Suffice to say just about anything can be a dependency: a local file, a directory of jars, another Gradle project, etc…, and dependencies can be configured to do things like exclude certain sub-dependencies.

Worth noting: Gradle and Maven do not resolve dependencies in exactly the same way. You can have the same set of dependencies in a Maven project and a Gradle project, and end up with dependency problems in one and not in the other.

For example, say we wanted to exclude the Log4j dependency from the Okta Spring Boot Starter, we could do this:

dependencies { implementation( 'com.okta.spring:okta-spring-boot-starter:1.2.1' ) { exclude group: 'org.apache.logging.log4j', module: 'log4j-api' }} |

Or say we wanted to include all the files in the libs directory as dependencies:

dependencies { implementation fileTree('libs')} |

The full notation is documented on the Gradle docs site for the DependencyHandler and in the Gradle docs for the Java plugin.

Wrapping A Gradle Build

One awesome thing about Gradle is the Gradle Wrapper. The Gradle command line is gradle. However, you’ll notice that in a lot of places online, you’ll see ./gradlew or gradlew.bat. These are commands that invoke the wrapper.

The wrapper allows a project to bundle the Gradle version necessary to build the project inside the project itself. This guarantees that changes to Gradle will not break the build because the correct version will always be available as well. It also ensures that people can run the build even if they do not have Gradle installed.

It adds the following files to your project:

├── gradle│ └── wrapper│ ├── gradle-wrapper.jar│ └── gradle-wrapper.properties├── gradlew└── gradlew.bat |

The gradlew and gradlew.bat are execution scripts for Linux/OSX and Window (respectively). They run the build.gradle file using the bundled Gradle .jar in the gradle/wrapper subdirectory.

This project was wrapped with Gradle version 5.5 and if you installed Gradle as suggested, you could likely run this project without a problem. However, you could just as easily do this entire tutorial using the wrapper.

Tasks, Tasks, and More Tasks

Tasks are at the core of Gradle. The Java plugin adds a dozen tasks, including: clean, compile, test, jar, and uploadArchives. The Spring Boot plugin adds the bootRun task, which runs the Spring Boot application.

Generally a task is run like this: gradle taskName otherTaskName, or using the wrapper: ./gradlew taskName otherTaskName.

If you open a terminal and cd to the base directory of the example project, you can use gradle tasks to list all of the tasks defined by the build.gradle file. tasks is, of course, itself a task defined by the base Gradle API.

> Task :tasks------------------------------------------------------------Tasks runnable from root project------------------------------------------------------------Application tasks-----------------bootRun - Runs this project as a Spring Boot application.Build tasks-----------assemble - Assembles the outputs of this project.bootJar - Assembles an executable jar archive containing the main classes and their dependencies.build - Assembles and tests this project.buildDependents - Assembles and tests this project and all projects that depend on it.buildNeeded - Assembles and tests this project and all projects it depends on.classes - Assembles main classes.clean - Deletes the build directory.jar - Assembles a jar archive containing the main classes.testClasses - Assembles test classes.Build Setup tasks-----------------init - Initializes a new Gradle build.wrapper - Generates Gradle wrapper files.Documentation tasks-------------------javadoc - Generates Javadoc API documentation for the main source code.Help tasks----------buildEnvironment - Displays all buildscript dependencies declared in root project 'SpringBootGradleProject'.components - Displays the components produced by root project 'SpringBootGradleProject'. [incubating]dependencies - Displays all dependencies declared in root project 'SpringBootGradleProject'.dependencyInsight - Displays the insight into a specific dependency in root project 'SpringBootGradleProject'.dependencyManagement - Displays the dependency management declared in root project 'SpringBootGradleProject'.dependentComponents - Displays the dependent components of components in root project 'SpringBootGradleProject'. [incubating]help - Displays a help message.model - Displays the configuration model of root project 'SpringBootGradleProject'. [incubating]projects - Displays the sub-projects of root project 'SpringBootGradleProject'.properties - Displays the properties of root project 'SpringBootGradleProject'.tasks - Displays the tasks runnable from root project 'SpringBootGradleProject'.Verification tasks------------------check - Runs all checks.test - Runs the unit tests.... |

I want to point out the dependencies task. It will list a tree with all dependencies (including sub-dependencies) required by the project. Try running gradle dependencies in the project root directory. You can drill down into a specific sub dependency using the dependencyInsight task.

Another helpful task for troubleshooting is the properties task, which lists all of the properties defined on the root project object instance.

Of course, when developing Spring Boot projects, 9 times out of 10, the command I use is: ./gradlew bootJar. This is a task added by the Spring Boot Gradle plugin that packages the project and it’s dependencies in a single jar file.

Creating Custom Tasks

Open your build.gradle file and add the following at the end:

println "1" task howdy { println "2" doLast { println "Howdy" } } println "3" |

This will demonstrate a little about how Gradle scripts work. Run it with:

./gradlew howdy |

You’ll see (with some extraneous lines omitted):

> Configure project :123> Task :howdyHowdy |

Here the Configure project task builds and runs the build script. As Gradle executes the Configure project task, it does the following:

- It hits the first

printlnand prints “1” - It finds the

howdytask definition block, a closure, which it executes, and prints “2”. Notice that it does not execute thedoLastclosure, so it does not yet print “A”. - It continues down the script, hitting the fourth

println, and prints “3”.

At this point, the build script itself has finished configuring the build environment. The next step is to execute any tasks specified on the command line, in our case thehowdy task.

This is where the task.doLast {} block gets executed, and thus you see “Howdy” printed in the output.

doLast is a misnomer for that block;what it really means it something like “task action”, while the outer block is task setup and configuration. See below.

task howdy { // always executed at during initial build script configuration doLast { // only executed if task itself is invoked } // always executed at during initial build script configuration } |

The various ways of defining tasks according to the Gradle docs using the Groovy DSL are as follows:

task taskNametask taskName { configure closure }task taskName(type: SomeType)task taskName(type: SomeType) { configure closure } |

Just to hammer this home, the “configure closure” is executed immediately when the build script runs and the doLast closure defined in the configure closure executes when the task is specifically performed.

Add a second custom task to the build.gradle file:

task partner { println "4" doLast { println "Partner" } } println "5" |

If you ./gradlew partner, you’ll see:

> Configure project :12345> Task :partnerPartner |

What if you want one custom task to depend on another? It’s easy. Add the following line somewhere in your build.gradle file after the definition of the two custom tasks.

partner.dependsOn howdy |

And run: ./gradlew partner

...> Task :howdyHowdy> Task :partnerPartner |

You could also have expressed a similar relationship using the task property finalizedBy. If you replace the dependsOn line with:

howdy.finalizedBy partner |

And run: /gradlew howdy.

...> Task :howdyHowdy> Task :partnerPartner |

Bam! Howdy partner.

You get the same output. Of course, they express different relationships.

There are a TON of options. This is partly where Gradle’s reputation for being confusing comes from. The Gradle docs for the Task API are a great reference.

One last point about tasks: in practice you rarely write custom tasks to say things like “Howdy Partner” (hard to believe, I know). In fact, typically you override an already defined task types. For example, Gradle defines a Copy task that copies files from one place to another.

Here’s an example that copies docs into the build target:

task copyDocs(type: Copy) { from 'src/main/doc' into 'build/target/doc'} |

The real power of Groovy and Gradle comes in when you realize that because the build.gradle file is actually a Groovy script, you can essentially execute arbitrary code to filter and transform these files, if you need to.

The task below transforms each copies file and excludes .DS_Store files. The DSL is super flexible. You can have multiple from blocks and excludes, or do things like rename files or specifically include files instead. Again, peek at the docs for the Copy task to get a fuller idea.

task copyDocs(type: Copy) { from 'src/main/doc' into 'build/target/doc' eachFile { file -> doSomething(file); } exclude '**/.DS_Store'} |

The task I override the most in Gradle Jar or War, the tasks responsible for packaging the .jar and .war files for final distribution. Like the Copy task, they have a very open-ended ability to customize the process, which can be a huge help on projects that require a customized final product. You can essentially use the Gradle DSL to totally control all aspects of the packaging process. (With great power comes great responsibility, of course).

The Spring Boot plugin’s bootJar and bootWar tasks inherit from the Jar and War tasks, so they include all of their configuration options, including the ability to copy, filter, and modify files, as well as the ability to customize the manifest.

Create an OIDC Application

Now that you’re an advanced Gradle ninja (or, at least, hopefully, not intimidated by the Gradle DSL), it’s time to go back to the original Spring Boot project.

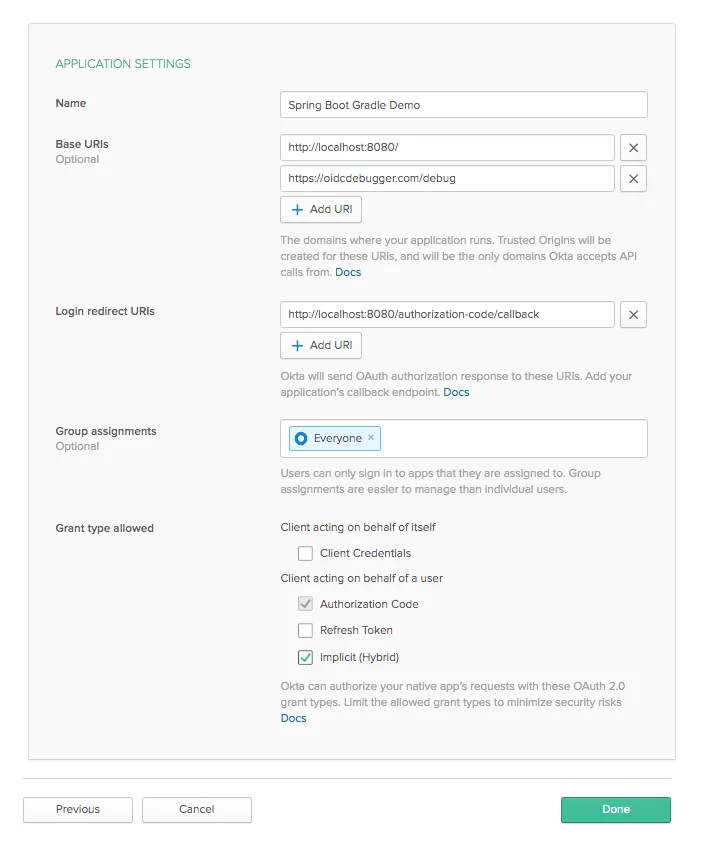

Go to your Okta developer dashboard to create an OpenID Connect application.

Click on the Application top menu. Click the Add Application button.

Select application type Web.

Click Next.

Give the app a name. I named mine “Spring Boot Gradle Demo”.

Under Login redirect URIs add the value: https://oidcdebugger.com/debug.

Under Grant type allowed, click the checkbox next to Implicit (Hybrid).

The rest of the default values will work.

Click Done.

Leave the page open of take note of the Client ID. You’ll need it in a moment to generate a JWT.

Update the Spring Boot App

You need to make a few changes to the Spring Boot app. First, remove all of the Howdy Partner stuff from the build.gradle file, if you want. It doesn’t actually hurt anything, but it’s not necessary anymore.

Add the following closure to the bottom of the build.gradle file:

processResources { expand(project.properties) } |

This configures the Java task to expand the project properties into the resource files.

If you take a look at the src/main/resources/application.yml file:

okta: oauth2: issuer: ${oauthIssuer} |

You’ll notice that there are two properties that we want to fill in. The best way to do this is with a gradle.properties file.

Create a gradle.properties file in the project root:

oauthIssuer={yourIssuerUri} |

You need to fill in the two values. The Client ID is from the OIDC app you just created. The Issuer URI will look like this: https://dev-123456.oktapreview.com/oauth2/default and can be found in the Okta developer dashboard. Go to API and select Authorization Servers. Look in the table for the default authorization server and the Issuer URI value.

Generate a Token Using OIDC Debugger

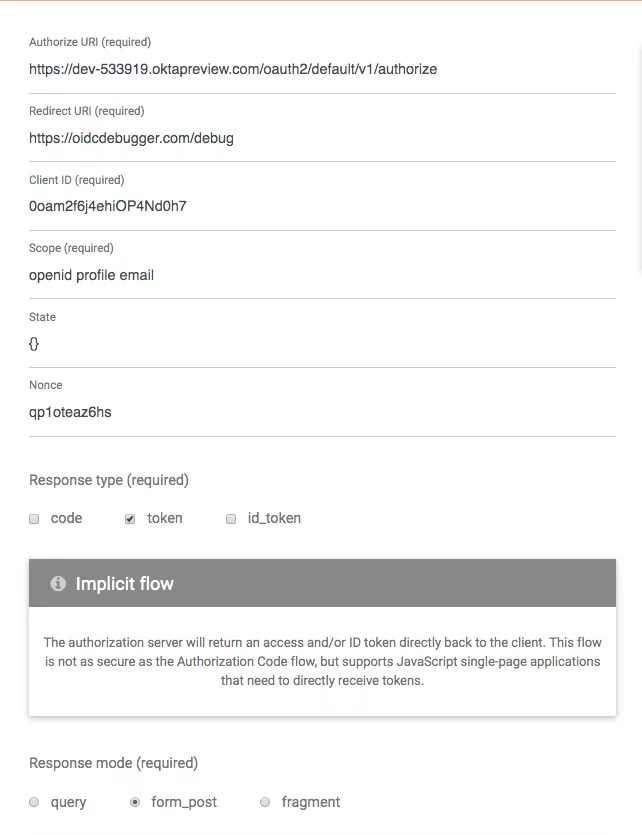

Use the OIDC Debugger to generate a token for your OIDC application.

You will need to fill in the:

- Authorize URI to match your Okta developer URI

- Client ID to match the OIDC app Client ID

- State to be anything, just not blank. In production, state helps prevent cross-site forgery requests and should be a CSRF Token.

Once you’ve done that, scroll down and click Send Request.

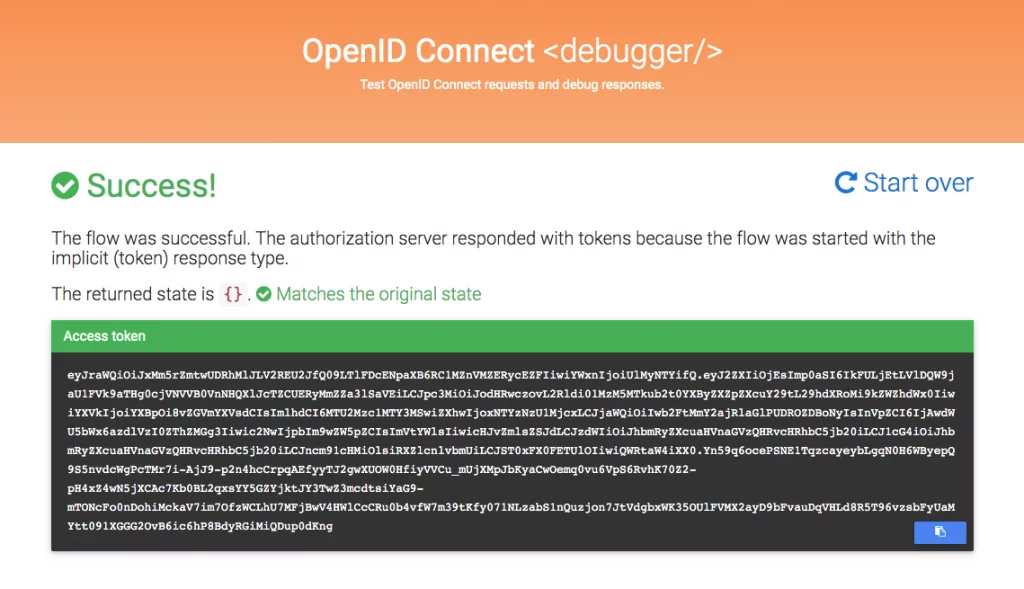

You should see the success screen.

Copy the access token, open a terminal, and store it in a shell variable like this:

export TOKEN=eyJraWQiOiJxMm5rZmtwUDRhMlJLV2REU2JfQ09LTlFD... |

Run a Request Using the Token

The Spring Boot app defines one controller: HelloController.java:

// ... @RestControllerpublic class HelloController { The Spring Boot app defines one contr // REQUIRES AUTHENTICATION @RequestMapping("/") public String home(java.security.Principal user) { return "Hello " + user.getName() + "!"; } // DOES NOT REQUIRE AUTHENTICATION @RequestMapping("/allow-anonymous") public String anonymous() { return "Hello whoever!"; } } |

There are two endpoints. Although it’s not obvious from the controller file itself, the / endpoint requires authentication and the /allow-anonymous endpoint does not. The configuration for this happens in the Application.java file, in the configure(HttpSecurity http) method. I’m glossing over the specifics of Spring Boot here because this isn’t the focus of this tutorial and is well covered in other blog posts (see the links at the end).

From a separate shell (not the one you just saved the TOKEN var in), run the Spring Boot app using:

./gradlew bootRun |

Back in the shell with the TOKEN var, run an HTTP request including the JWT:

http :8080 "Authorization: Bearer $TOKEN" |

You’ll get an HTTP 200:

HTTP/1.1 200Cache-Control: no-cache, no-store, max-age=0, must-revalidate...Hello andrew.hughes@example.com! |

Success!

You can run a request without the JWT to see that auth is required:

http :8080 |

HTTP/1.1 401Cache-Control: no-cache, no-store, max-age=0, must-revalidateContent-Length: 0... |

For more detail on the Spring Boot app and authentication/authorization, check out the links at the end for more blog posts.

The next step is to write a couple tests and run them with Gradle.

Test the Code

Create a test file: src/test/java/com/okta/springbootgradle/HelloControllerTest.java

package com.okta.springbootgradle; import org.junit.Test; import org.junit.runner.RunWith; import org.springframework.beans.factory.annotation.Autowired; import org.springframework.boot.test.autoconfigure.web.servlet.AutoConfigureMockMvc; import org.springframework.boot.test.context.SpringBootTest; import org.springframework.boot.test.context.SpringBootTest.WebEnvironment; import org.springframework.boot.web.server.LocalServerPort; import org.springframework.test.context.junit4.SpringRunner; import org.springframework.test.web.servlet.MockMvc; import static org.hamcrest.Matchers.containsString; import static org.springframework.security.test.web.servlet.request.SecurityMockMvcRequestPostProcessors.user; import static org.springframework.test.web.servlet.request.MockMvcRequestBuilders.get; import static org.springframework.test.web.servlet.result.MockMvcResultHandlers.print; import static org.springframework.test.web.servlet.result.MockMvcResultMatchers.content; import static org.springframework.test.web.servlet.result.MockMvcResultMatchers.status; @RunWith(SpringRunner.class) @SpringBootTest(webEnvironment = WebEnvironment.RANDOM_PORT, properties = {"okta.oauth2.issuer=https://oauth.example.com/oauth2/default"}) @AutoConfigureMockMvc public class HelloControllerTest { @LocalServerPort private int port; @Autowired private MockMvc mockMvc; // test for auth required on home endpoine @Test public void homeShouldFail() throws Exception { this.mockMvc .perform(get("/")) .andDo(print()) .andExpect(status().isUnauthorized()); } // test home endpoint with auth @Test public void homeShouldPass() throws Exception { this.mockMvc .perform(get("/").with(user("Mister Tester"))) .andDo(print()) .andExpect(status().isOk()) .andExpect(content().string(containsString("Hello Mister Tester!"))); } // test anonymous endpoint @Test public void anonymous() throws Exception { this.mockMvc .perform(get("/allow-anonymous")) .andDo(print()) .andExpect(status().isOk()) .andExpect(content().string(containsString("Hello whoever!")));; } } |

This test file has three tests. The first test checks the home endpoint to ensure that a request that does not supply authentication fails with an unauthorized error. The second test uses the Spring MockMVC library to supply authentication and tests the home endpoint again. The last test checks the /allow-anonymous endpoint.

Run the tests with: ./gradlew test

The output is pretty minimal:

> Task :testINFO [Thread-6] o.s.s.c.ThreadPoolTaskExecutor : Shutting down ExecutorService 'applicationTaskExecutor'BUILD SUCCESSFUL in 7s5 actionable tasks: 5 executed |

If you’d like to see more info, try adding the -i flag, like so:

./gradlew test -i |

Testing with Spring is a whole tutorial in itself, so I’ll leave it at that. Spring’s nice guide introduces some different ways to test Spring Boot REST services.

I would never, ever condone this, but if you need to run a build and want to skip the tests, you can use: gradle build -x test.

Like all things Gradle, the Test task is highly customizable. You can set test-specific system properties, configure JVM args, change heap sizes, include or exclude specifics tests, etc… Take a look at the docs for the Test task on the Gradle page.

You can also check out the final state of the project on the GitHub page on the master branch.

Wrapping Up

In this tutorial you learned the basics of the Gradle build system. You saw that Gradle is super flexible and customizable and can be used with a Groovy DSL or Kotlin DSL. You looked at the sample build.gradle file in the tutorial project and saw how a typical build is configured. Next, the tutorial dove into the world of closures and saw how they are used in the Gradle DSL to create configuration blocks. After that, you used the Gradle wrapper to encapsulate the project build system within the project itself and then dove into Gradle tasks, creating custom tasks and looking how tasks are processed and executed. And there’s more! Haha. The tutorial then showed you how to build and run a simple Spring Boot project using Gradle, and how to define and run a few tests using Spring and Gradle.

As promised, the Okta blog has tons of great tutorials if you’d like to learn more about Spring Boot and Java:

- Simple Token Authentication for Java Apps

- Servlet Authentication with Java

- Build a Web App with Spring Boot and Spring Security in 15 Minutes

- Build a REST API Using Java, MicroProfile, and JWT Authentication

- Create a Secure Spring REST API

- Build a Simple CRUD App with Spring Boot and Vue.js

If you enjoyed this post, follow us on social media { Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, YouTube } to know when we’ve posted ones like it.

Get Groovy with Gradle was originally published on the Okta Developer Blog on September 07, 2019.

Friends don’t let friends write user auth. Tired of managing your own users? Try Okta’s API and Java SDKs today. Authenticate, manage, and secure users in any application within minutes.