Scaling Scala vs Java

In my previous post I showed how it makes no sense to benchmark Scala against Java, and concluded by saying that when it comes to performance, the question you should be asking is ‘How will Scala help me when my servers are falling over from unanticipated load?’ In this post I will seek to answer that, and show that indeed Scala is a far better language for building scalable systems than Java.

However, don’t expect our journey to get there to be easy. For a start, while it’s very easy to do micro benchmarks, trying to show how real world apps do or don’t handle the loads that are put on them is very hard, because it’s very hard to create an app that’s small enough to demo and explain in a single blog post that is at the same time big enough to actually show how real world apps behave under load, and it’s also very hard to simulate real world loads. So I am going to take one small aspect of something that might go wrong in the real world, and show just one way in which Scala will help you, where Java won’t. Then I will explain that this is just the tip of the iceberg, there are far more situations, and far more features of Scala that will help you in the real world.

An online store

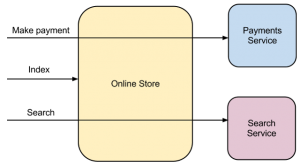

For this exercise I have implemented an online store. The architecture of this store is in the diagram below:

As you can see, there is a payment service and a search service that the store talks to, and the store handles three types of requests, one for the index page that doesn’t require going to any other services, one for making payments that uses the payments service, and another for searching the stores product list which uses the search service. The online store is the part of the system that I am going to be benchmarking, I will implement one version in Java, and another in Scala, and compare them. The search and payment services won’t change. Their actual implementations will be simple JSON APIs that return hard coded values, but they will each simulate a processing time of 20ms.

For the Java implementation of the store, I am going to keep it as simple as possible, using straight servlets to handle requests, Apache Commons HTTP client for making requests, and Jackson for JSON parsing and formatting. I will deploy the application to Tomcat, and configure Tomcat with the NIO connector, using the default connection limit of 10000 and thread pool size of 200.

For the Scala implementation I will use Play Framework 2.1, using the Play WS API which is backed by the Ning HTTP client to make requests, and the Play JSON API which is backed by Jackson to handle JSON parsing and formatting. Play Framework is built using Netty which has no connection limit, and uses Akka for thread pooling, and I have it configured to use the default thread pool size, which is one thread per CPU, and my machine has 4.

The benchmark I will be performing will be using JMeter. For each request type (index, payments and search) I will have 300 threads spinning in a loop making requests with a random 500-1500ms pause in between each request. This gives an average maximum throughput of 300 requests per second per request type, or 900 requests per second all up.

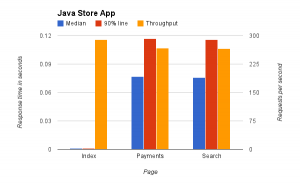

So, let’s have a look at the result of the Java benchmark:

On this graph I have plotted 3 metrics per request type. The median is the median request time. For the index page, this is next to nothing, for the search and payments requests, this is about 77ms. I have also plotted the 90% line, which is a common metric in web applications, it shows what 90% of the requests were under, and so gives a good idea of what the slow requests are like. This shows again almost nothing for the index page, and 116ms for the search and payments requests. The final metric is the throughput, which shows number of requests per second that were handled. We are not too far off the theoretical maximum, with the index showing 290 requests per second, and the search and payments requests coming through at about 270 requests per second. These results are good, our Java service handles the load we are throwing at it without a sweat.

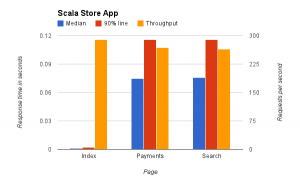

Now let’s take a look at the Scala benchmark:

As you can see, it’s identical to the Java results. This is not surprising, since both the Java and the Scala implementations of the online store are doing absolutely minimal work code wise, most of the processing time is going in to making requests on the remote services.

Something goes wrong

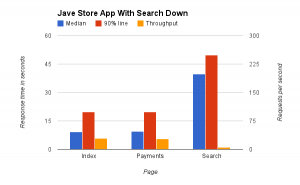

So, we’ve seen two happy implementations of the same thing in Scala and Java, shrugging off the load I give them. But what happens when things aren’t so fine and dandy? What happens if one of the services that they are talking to goes down? Let’s say the search service starts taking 30 seconds to respond, after which point it returns an error. This is not an unusual failure situation, particularly if you’re load balancing through a proxy, the proxy tries to connect to the service, and fails after 30 seconds, giving you a gateway error. Let’s see how our applications handle the load I throw at them now. We would expect the search request to take at least 30 seconds to respond, but what about the others? Here’s the Java results:

Well, we no longer have a happy app at all. The search requests are naturally taking a long time, but the payments service is now taking an average of 9 seconds to respond, the 90% line is at 20 seconds. Not only that, but the index page is similarly impacted – users are not going to be waiting that long if they’ve browsed into your site for the home page to show up. And the throughput of each has gone down to 30 requests per second. This is not good, because your search service went down, your whole site is now practically unusable, and you will soon start losing customers and money.

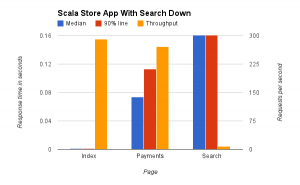

So how does our Scala app fair? Let’s find out:

Now before I say anything else, let me point out that I’ve bounded the response time to 160ms – the search requests are actually taking about 30 seconds to respond, but on the graph, with 30 seconds next to the other values, they hardly register a line a pixel high. So what we can see here is that while search is unusable, our payments and index request response times and throughput are unchanged. Obviously, customers aren’t going to be happy with not being able to do searches, but at least they can still use other parts of your site, see your home page with specials, and even still make payments for items. And hey, Google isn’t down, they can always use Google to search your site. So you might lose some business, but the impact is limited.

So, in this benchmark, we can see that Scala wins hands down. When things start to go wrong, a Scala application will take it in it’s stride, giving you the best it can, while a Java application will likely just fall over.

But I can do that in Java

Now starts the bit where I counter the many anticipated criticisms that people will make of this benchmark. And the first, and most obvious one, is that in my Scala solution I used asynchronous IO, whereas in my Java solution I didn’t, so they can’t be compared. It is true, I could have implemented an asynchronous solution in Java, and in that case the Java results would have been identical to the Scala results. However, while I could have done that, Java developers don’t do that. It’s not that they can’t, it’s that they don’t. I have written a lot of webapps in Java that make calls to other systems, and very rarely, and only in very special circumstances, have I ever used asynchronous IO. And let me show you why.

Let’s say you have to do a series of calls on a series of remote services, each one depending on data returned from the previous. Here’s a good old fashioned synchronous solution in Java:

User user = getUserById(id); List<Order> orders = getOrdersForUser(user.email); List<Product> products = getProductsForOrders(orders); List<Stock> stock = getStockForProducts(products);

The above code is simple, easy to read, and feels completely natural for a Java developer to write. For completeness, let’s have a look at the same thing in Scala:

val user = getUserById(id) val orders = getOrdersForUser(user.email) val products = getProductsForOrders(orders) val stock = getStockForProducts(products)

Now, let’s have a look at the same code, but this time assuming we are making asynchronous calls and returning the results in promises. What does it look like in Java?

Promise<User> user = getUserById(id);

Promise<List<Order>> orders = user.flatMap(new Function<User, List<Order>>() {

public Promise<List<Order>> apply(User user) {

return getOrdersForUser(user.email);

}

}

Promise<List<Product>> products = orders.flatMap(new Function<List<Order>, List<Product>>() {

public Promise<List<Product>> apply(List<Order> orders) {

return getProductsForOrders(orders);

}

}

Promise<List<Stock>> stock = products.flatMap(new Function<List<Product>, List<Stock>>() {

public Promise<List<Stock>> apply(List<Product> products) {

return getStockForProducts(products);

}

}So firstly, the above code is not readable, in fact it’s much harder to follow, there is a massively high noise level to actual code that does stuff, and hence it’s very easy to make mistakes and miss things. Secondly, it’s tedious to write, no developer wants to write code that looks like that, I hate doing it. Any developer that wants to write their whole app like that is insane. And finally, it just doesn’t feel natural, it’s not the way you do things in Java, it’s not idiomatic, it doesn’t play well with the rest of the Java ecosystem, third party libraries don’t integrate well with this style. As I said before, Java developers can write code that does this, but they don’t, and as you can see, they don’t for good reason.

So let’s take a look at the asynchronous solution in Scala:

for {

user <- getUserById(id)

orders <- getOrdersForUser(user.email)

products <- getProductsForOrders(orders)

stock <- getStockForProducts(products)

} yield stockIn contrast to the Java asynchronous solution, this solution is completely readable, just as readable as the Scala and Java synchronous solutions. And this isn’t just some weird Scala feature that most Scala developers never touch, this is how a typical Scala developer writes code every day. Scala libraries are designed to work using these idioms, it feels natural, the language is working with you. It’s fun to write code like this in Scala!

This post is not about how with one language you can write a highly tuned app for performance that’s faster than the same app written in another language highly tuned for performance. This post is about how Scala helps you write applications that are scalable by default, using natural, readable and idiomatic code. Just like a ball in lawn bowls has a bias, Scala has a bias to helping you write scalable applications, where Java makes you swim upstream.

But scaling means so much more than that

The example I’ve provided of Scala scaling well where Java doesn’t is a very specific example, but then what situation where your app is failing under high load isn’t? Let me give a few other examples of where Scala’s much nicer asynchronous IO support helps you to write scalable code:

- Using Akka, you can easily define actors for different types of requests, and allocate them different resource limits. So if certain parts of your single application start struggling or receiving unanticipated load, those parts may stop responding, but the rest of your app can stay healthy.

- Scala, Play and Akka make handling single requests using multiple threads running in parallel doing different operations incredibly simple, allowing you to have requests that do a lot in very little time. Klout wrote an excellent article about how they did just that in their API.

- Because asynchronous IO is so simple, offloading processing onto other machines can be safely done without tying up threads on the first machine.

Java 8 will make asynchronous IO simple in Java

Java 8 is probably going to include support for closures of some sort, which is great news for the Java world, especially if you want to do asynchronous IO. However, the syntax still won’t be anywhere near is readable as the Scala code I showed above. And when will Java 8 be released? Java 7 was released last year, and it took 5 years to release that. Java 8 is scheduled for summer 2013, but even if it arrives on schedule, how long will it take for the ecosystem to catch up? And how long will it take for Java developers to switch from a synchronous to an asynchronous mindset? In my opinion, Java 8 is too little too late.

So this is all about asynchronous IO?

So far all I’ve talked about and shown is how easy Scala makes asynchronous IO, and how that helps you scale. But it doesn’t stop there. Let me pick another feature of Scala, immutability.

When you start using multiple threads to process single requests, you start sharing state between those threads. And this is where things get very messy, because the world of shared state in a computer system is a crazy world where impossible things happen. It’s a world of deadlocks, a world of updating memory in one thread, but another thread not seeing that change, a world of race conditions, and a world of performance bottle necks because you over eagerly marked some methods as synchronized.

However, it’s not that bad, because there is a very simple solution, make all your state immutable. If all your state is immutable, then none of the above problems can happen. And this is again where Scala helps you big time, because in Scala, things are immutable by default. The collection APIs are immutable, you have to explicitly ask for a mutable collection in order to get mutable collections.

Now in Java, you can make things immutable. There are some libraries that help you (albeit clumsily) to work with immutable collections. But it’s so easy to accidentally forget to make something mutable. The Java API and language itself don’t make working with immutable structures easy, and if you’re using a third party library, it’s highly likely that it’s not using immutable structures, and often requires you to use mutable structures, for example, JPA requires this.

Let’s have a look at some code. Here is an immutable class in Scala:

case class User(id: Long, name: String, email: String)

That structure is immutable. Moreover, it automatically generates accessors for the properties. Let’s look at the corresponding Java:

public class User {

private final long id;

private final String name;

private final String email;

public User(long id, String name, String email) {

this.id = id;

this.name = name;

this.email = email;

}

public long getId() {

return id;

}

public String getName() {

return name;

}

public String getEmail() {

return email

}

}That’s an enormous amount of code! And what if I add a new property? I have to add a new parameter to my constructor which will break existing code, or I have to define a second constructor. In Scala I can just do this:

case class User(id: Long, name: String, email: String, company: Option[Company] = None)

All my existing code that calls that constructor will still work. And what about when this object grows to have 10 items in the constructor, constructing it becomes a nightmare! A solution to this in Java is to use the builder pattern, which more than doubles the amount of code you have to write for the object. In Scala, you can name the parameters, so it’s easy to see which parameter is which, and they don’t have to be in the right order. But maybe I might want to just modify one property. This can be done in Scala like this:

case class User(id: Long, name: String, email: String, company: Option[Company] = None) {

def copy(id: Long = id, name: String = name, email: String = email, company: Option[Company] = company) = User(id, name, email, company)

}

val james = User(1, 'James', 'james@jazzy.id.au')

val jamesWithCompany = james.copy(company = Some(Company('Typesafe')))The above code is natural, it’s simple, it’s readable, it’s how Scala developers write code every day, and it’s immutable. It is aptly suited to concurrent code, and allows you to safely write systems that scale. The same can be done in Java, but it’s tedious, and not at all a joy to write. I am a big advocate of immutable code in Java, and I have written many immutable classes in Java, and it hurts, but it’s the lesser of two hurts. In Scala, it takes more code to use mutable objects than to use immutable. Again, Scala is biased towards helping you scale.

Conclusion

I cannot possibly go into all the ways in which Scala helps you scale where Java doesn’t. But I hope I have given you a taste of why Scala is on your side when it comes to writing Scalable systems. I’ve shown some concrete metrics, I’ve compared Java and Scala solutions for writing scalable code, and I’ve shown, not that Scala systems will always scale better than Java systems, but rather that Scala is the language that is on your side when writing scalable systems. It is biased towards scaling, it encourages practices that help you scale. Java, in contrast, makes it difficult for you to implement these practices, it works against you.

If you’re interested in my code for the online store, you can find it in this GitHub repository. The numbers from my performance test can be found in this spreadsheet.

Reference: Scaling Scala vs Java from our JCG partner James Roper at the James and Beth Roper’s blogs blog.