You Won’t Believe What These Five Lenses Can Show You About Your Product

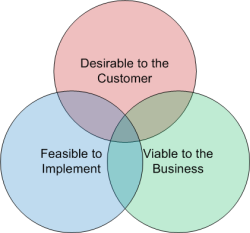

Fundamentally, product management requires you to assess, synthesize, and prioritize the needs which drive the creation of your product in the context of three main objectives: desirability, viability, and feasibility. While laudable, these objectives are too abstract to be actionable. That’s where the five lenses come in (I could not resist the Buzzfeed-styled title).

The Product Strategy Grid

Steven Haines wrote The Product Manager’s Desk Reference, and from (the first edition of) his book I learned about the product strategy grid. Over the years, I may have tweaked it to serve my needs, or used it a little differently than he presents – honestly, I don’t remember – but I believe that I am staying with the spirit of what he originally described for us several years ago.

As a product manager, we build roadmaps to help communicate to the team building the product, a set of instructions / goals / themes designed to manifest the product strategy. I believe the product strategy grid is a fantastic tool for

- Aligning your organization around a definition of the product strategy, given the company’s objectives and perspective on the future

- Clearly articulating the expectations the leadership team has – the measures by which “success” is defined for the product

- Establishing an accountable expectation of the outcomes which are anticipated by the product manager for a given investment (aka roadmap)

- Communicating a shared view of the future – beyond the immediate scope of delivery – with the entire team

The other day, with a client, I made this statement: I believe the product manager is entitled to know the measures of success, when being asked to build the roadmap.

The product strategy grid is too much to cover in a single blog post – even the long ones I tend to write. I do a multi-day workshop to define what it means for a particular team. Conceptually, I can walk an engaged and enthusiastic team through it in two hours. I know this because I’ve tried (and failed) to do it in one hour.

For this article, I’m only going to talk about five lenses – the key to how I build out a product strategy grid (lenses translate to rows in the grid). There may be better ways, but this one works. Really works. So thank you Steven for starting me down this path.

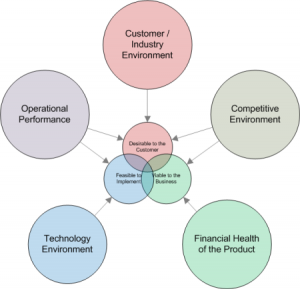

Five Lenses

Some day I may feel six lenses, or four lenses, to be better than five. When using this technique at the portfolio level, I’ve used seven lenses to understand and assess not only the per-product context, but the context of the firm and how they take a portfolio of products to the market. But for now, there are five.

I guess I should describe what I mean by the word lens. This is the kind of corporate jargon that creeps into conversation and eventually shows up on someone’s meeting-bingo card. In this context, I mean a lens to be something you use to view your product from a particular perspective. Some investments we make in a product are important because of their impact on our competitive position. Other investments are important to reducing costs or achieving revenue goals.

Applying lenses to how we view our product allows us to avoid the problem of the blind men and the elephant. As an organizational bonus, it allows different stakeholders with specific areas of responsibility and interest to both contribute to the conversation, and develop a shared understanding of a holistic perspective on the product.

Looking AT Each Lens

I’m not trying to tackle the full breadth and power of the product strategy grid in this article. Each lens reflects a “row” in the grid. There’s more stuff defining columns.

Let’s take a look at each lens. One thing you’ll notice – some lenses have arrows pointing to two objectives (the competitive environment lens points to both desirability and viability), where some point to a single objective. This is a reflection of my attempt to align lenses with the areas of focus in an organization by which people tend to have a sense of ownership of things.

Jeff Patton talks elegantly about reaching shared understanding (in User Story Mapping) – which is absolutely an intended outcome of using these lenses to organize views of the product strategy. I also believe a team will be more effective when there are champions who feel deep connections with what everyone should look for (and see) through each lens.

Customer Environment

The customer lens is the one you look through when you are asking “who is my customer?” and “what problem are they trying to solve?”

When we talk about markets changing, targeting specific personas, and understanding problems, this is where we view the understanding we develop. When discussing the inclusion of a particular feature in the product, we can look through through this lens and ask questions.

- Would this feature help one of our target personas to solve a problem they care about?

- To what degree of completeness / goodness / done-ness should we address this problem?

Competitive Environment

When you want to know if your product is “better” than your competitors, this is the lens you look through.

Conversations around relative market position, comparing our product with competitors happen here too. We can ask specific questions here

- What are the relative price and value of our product and our competitors products?

- For the most important problem in our most important market, how does our product compare?

Financial Health of the Product

Being objectively better for our customers does not necessarily mean our product is “good.” In investing, there’s a phrase – “a good company can be a bad investment.” There’s an analog to be found in product management.

Our focus is on our customers, but it is not myopically so. A product is expected to meet a set of financial objectives which justify investing in the product in the first place. The specific questions being asked do vary from company to company. They could be items like

- What percentage of revenue is coming from sales of new products to existing customers, versus existing (subscription, maintenance, etc) product revenue?

- What is the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of our free cash flow?

- What is our churn (or retention) rate for customers in the current year cohort versus last year’s cohort?

Technology Environment

This is a great lens for the champion of the technology team to stand up and say “we need to improve our capability to deliver capabilities” and have it make sense.

You can build a business on a house of cards, or shifting sand, or baling twine – or any other metaphor you desire for “it will all fall apart at some point.” It would be nice to know when it will fall apart. It would be even better to change this state (and know it), or prevent it from happening at all. Interesting questions tend to be a function of “what specifically has been hurting us recently?”

- What percentage of our investments in quality (e.g. cost of quality) are reactive, versus proactive?

- How many versions of the product are we simultaneously supporting in the field?

- What is the 90% time* for customers getting fixes to sev-1 and sev-2 bugs deployed in their environments?

*90% time is the time by which 90% of all fixes have been deployed. The average time is not nearly as reflective of how well you are serving your customers. Also note that the measurement is from “reported by customer” to “resolved for customer” and not “validated by QA” to “promoted to trunk by dev.”

Operational Performance

In enterprise software, it isn’t enough to build software, you have to deploy it. That might take months. You might be building a business on which the ability to scale is a key assumption of the business case.

The outside-in notion of understanding how your customer defines success (at solving the problem for which they would be using your product) has a nice home here.

You can ask questions like

- How many man-weeks of effort and calendar-weeks of time are required to deploy the product? [This is another great place for the 90% time]

- How much faster must our customer’s invoice-processing process be, for them to consider themselves successful?

Conclusion

Each lens provides a perspective on aspects of the product strategy, always relevant to everyone – and often particularly relevant to someone specific. Combined, the lenses provide the context in which a product manager makes their investment decisions.

The team relies on the product manager to “give them a backlog” and assumes the backlog is identifying the right things to be building. The definition of right things is a function of product strategy.

How do you know if you have the right product strategy? The answers are visible through these five lenses. Now do you believe what they can show you?

| Reference: | You Won’t Believe What These Five Lenses Can Show You About Your Product from our JCG partner Scott Sehlhorst at the Tyner Blain’s blog blog. |