Preparing your career for the data science revolution

I became familiar with Geoffrey Moore in 2002, while consulting at Symbol Technologies, helping it transform from a product-only company into a solutions company (that is, both products and services). The president of Symbol mentioned Moore’s work, and he often used the terms “core” and “context” when describing Symbol’s business operations. As I began reading Moore, his ideas crystallized in my mind, developing in me a growing appreciation for his work.

Innovating in a complex business environment

In 2005, Moore published Dealing with Darwin, offering a glimpse into how companies innovate during each phase of their evolution. Moore paints the picture of a business environment that is ever more competitive, globalized, deregulated and commoditized. Unsurprisingly, the combination of these forces puts immense pressure on companies to find ways of innovating in an increasingly complex environment.

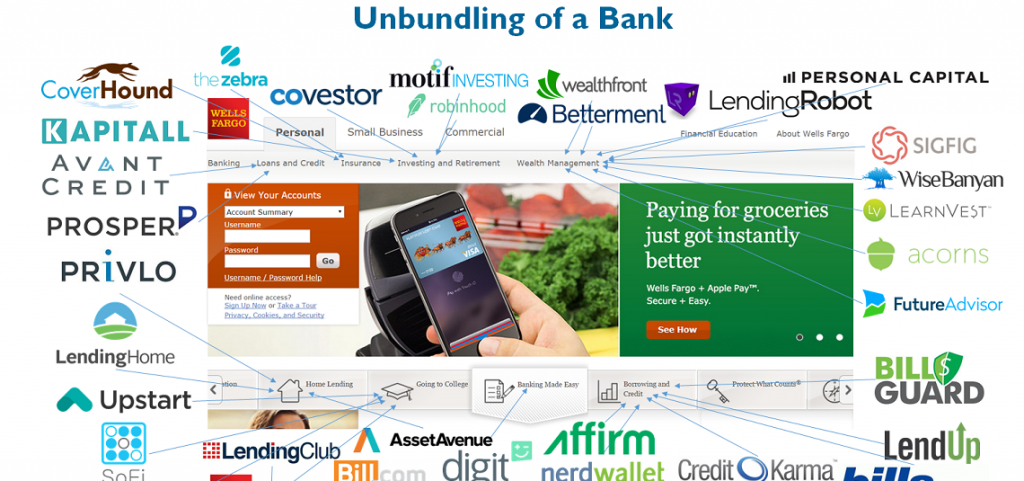

Back in 2005, not all those forces were pronounced, but they have since become indisputably so. Indeed, not only are they present, but they are beginning to make many large companies irrelevant. The unbundling chart in Figure 1 demonstrates:

Competition and innovation have been forever changed. But such forces’ effects on companies merely marked a beginning. The next assault will be on individuals within companies. In the next five years, every employee will be dealing with Darwin personally.

Individuals first dealt with Darwin on substantial levels during the Industrial Revolution, continuing through the rest of the 1900s, when factories began replacing traditional small industries. As factories appeared, demand for labor heightened. But factory work was quite different from traditional work and quickly became known for its poor working conditions. Even worse, because most factory work did not require a particular strength or skill of its workers, workers were considered unskilled and were thus easily replaceable. At first, factory workers were replaced by other workers, but eventually they were automated away, forcing them to move to lower-cost countries.

Shifting roles in the workforce

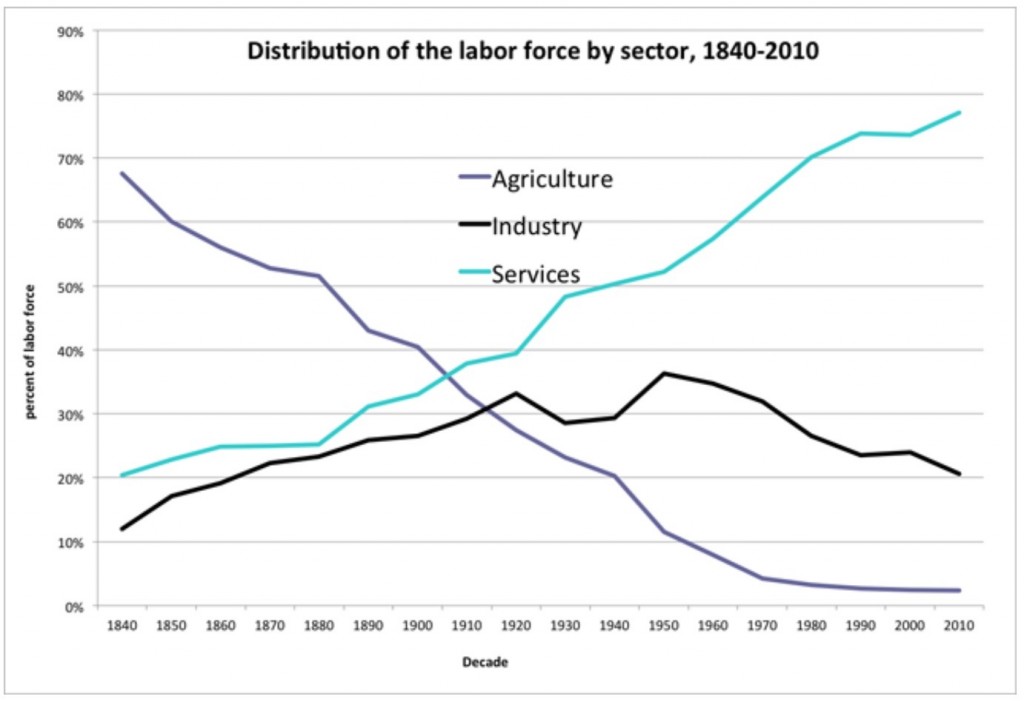

Economists typically categorize three kinds of work in a country: agriculture (farming), industry (manufacturing) and services. Each type of work plays a role in the economy, but macroeconomic forces have changed the mix over time. As seen in Figure 2, although 70 percent of the labor force worked in agriculture in 1840, the agricultural share reduced to 40 percent by 1900 and today sits at a mere 2 percent. Such shifts force employees to adapt, dealing with Darwin at a very personal level.

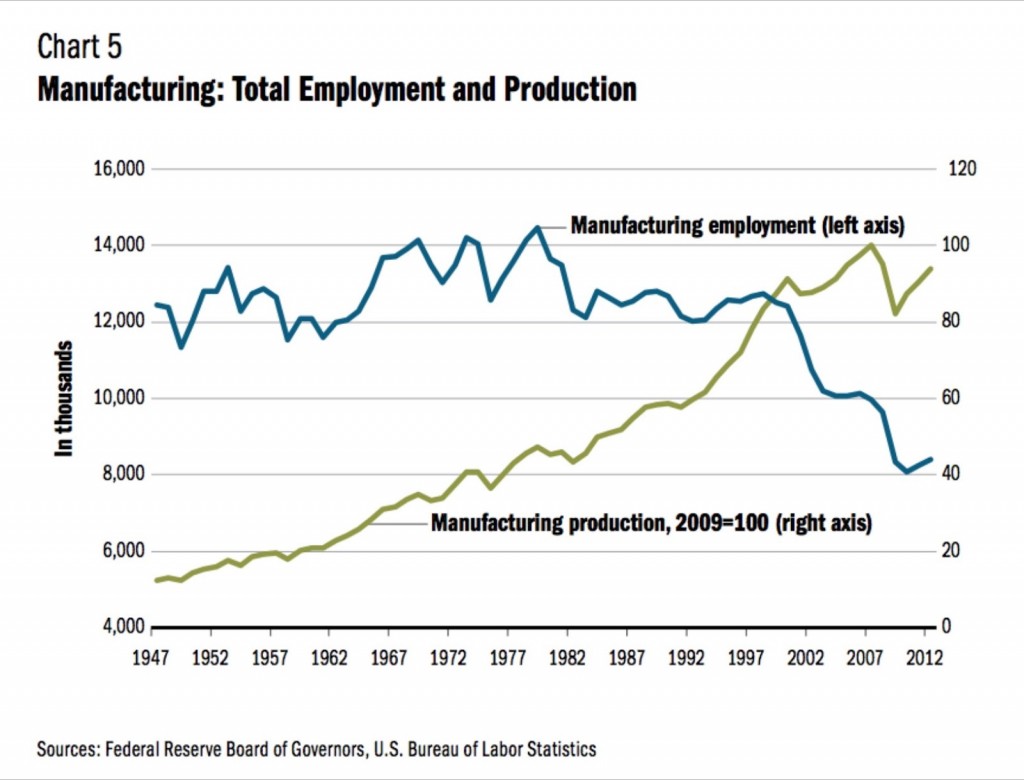

As Figure 3 shows, this shift has accelerated in the past 15 years, a period during which productivity has exploded:

Clearly, Darwin has struck at traditional workers and approaches. Thanks to widespread automation, broad acceptance of best practices and experience, skills that were once valued—and, indeed, that were necessary for industry—have been reduced to commodity services. Could the same thing happen to traditional IT jobs?

Redefining the skilled worker

In Big data revolution: what farmers, doctors, and insurance agents teach us about discovering big data patterns, I identify 54 big data patterns across a variety of industries. Whether you are a retailer, an insurance agent, a commercial banker or a doctor, these patterns will affect your role and the industry in which you play it. One pattern I identify is that of redefining the skilled worker:

The data era is demanding a new definition of skilled workers. While this may require skills like statistics or math, that is merely one aspect of the skill gap that must be filled. In medicine, it’s about redefining medical school to include skills like data analysis and data collection. In farming, the new skill set involves understanding how to utilize multiple sources of data (from drones, GPS, or otherwise) and apply that insight to deliver better yields and productivity.

The definition of a skilled worker has changed dramatically, based on different eras. In the 1700s and 1800s, skilled workers were defined by either their physical abilities or their knowledge of a certain craft (think bookkeeper). At the time of the Industrial Revolution, skilled workers were defined by their physical capacity to operate a machine or work on an assembly line. In the last 20 years, skilled workers have evolved further, with a premium placed on customer service and technology skills.

A skilled worker in the next decade will be defined by her ability to acquire, analyze, and utilize data and information. This new skilled worker will emerge in every industry, with a slightly different definition of the skill set for each industry.

The key patterns to redefine a skilled worker are

- Understanding the skill sets needed today, tomorrow, and further in the future, based on the potential for data disruption.

- Redefining roles and skill sets to take advantage of the new data available that can impact business processes.

- Training and retraining current and new workers is a distinguishing capability to remain relevant.

An organization must accept that the skills they have today may not be sufficient for the data era. The challenge is that the skill gaps, once understood, will likely prove to be excessively broad. The data era demands skills in data science, statistics, and probability. And that’s just on the business side. On the IT side, the skill needs are much different than traditional IT, with a premium placed on programming and modeling skills. Leading organizations will document their skills today versus the skills needed tomorrow and systematically begin to fill the inevitable gaps.

Though companies must understand their skill gaps and solve them at a company level, the challenge for individuals is even more pressing: What skill will you master? What skill aligns with the data era? For what craft will you be known? I believe that data science is the answer to all three questions.

Taking the cloud into account

The cloud has profoundly affected IT. Although moving to the cloud can help diminish the costs of starting a company and can help cut capital expenses, I believe that the cloud’s bigger effect will be on the traditional definition of a skilled IT worker. As organizations move to the cloud, I expect the importance of traditional IT roles and skills—systems administrator, architect, DBA, IT operations—to diminish or even be eliminated over the next 5 to 10 years. Make no mistake: I think this shift will take a long time to play out. But such a belief means that now is the time to prepare for the coming revolution.

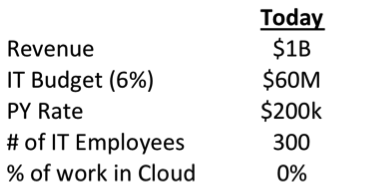

Let’s imagine an organization having revenue of $1 billion, and let’s assume that it spends 6 percent of its revenue per year on IT. Figure 4 shows some related factors that we can calculate under such an assumption:

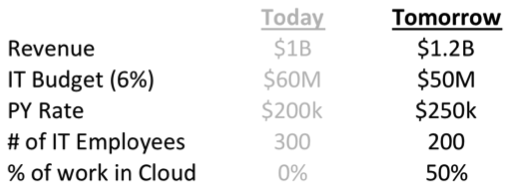

For such a company, the decision to shift to the cloud will be predicated on increasing leverage and efficiency and will force a rethinking of the workforce. There is good news—salaries of the employees will go up as they acquire rare and sophisticated skills—but as Figure 5 depicts, there is also bad: Traditional IT skills will be less in demand, for much such work will have been shifted to the cloud.

This shift presents both pitfall and opportunity for individuals. Indeed, the greatest risk lies in doing nothing—in merely continuing business as usual. More tools and education are available than ever have been for individuals who decide that they want to be leaders in the data era. To be blunt: Data science will be the data era’s defining skill. Though traditional IT skills will remain important for some, such skills will be increasingly less relevant in the cloud-centric data era.

| Reference: | Preparing your career for the data science revolution from our JCG partner Rob Thomas at the Rob’s Blog blog. |