Decision Time: How Decision Rules Help You Make Better Product Decisions

As product managers and product owners, we make a myriad of decisions—from shaping the product strategy and determining the product roadmap to deciding the detailed functionality of our products. But do we make all these decisions effectively? And do we always secure the necessary buy-in? This post helps you make better decisions. It discusses five common decision rules and explains when to apply them.

Decisions, Decisions

“Is everybody OK with changing the release goal for Q3?”, asks Julie, the product manager. After a few seconds of silence, Julie moves on to the next topic assuming that the stakeholders agree. But most people are still thinking about the idea or oppose it. What’s more, nobody really knows who makes the final decision. Is it the product manager, the people present, or the management sponsor?

If it’s unclear how a decision is made and whose input is required, people will be unsure if a decision has actually been made and if it should be actioned. Some people will start to implement the decision, while others ignore it instead of following it through.

If you want people to move together in the same direction, you need to give them a clear indicator if a decision has been made: you should clearly state how the decision is reached and whose input is required. In other words, you should apply the right decision rule.

Decision Rules

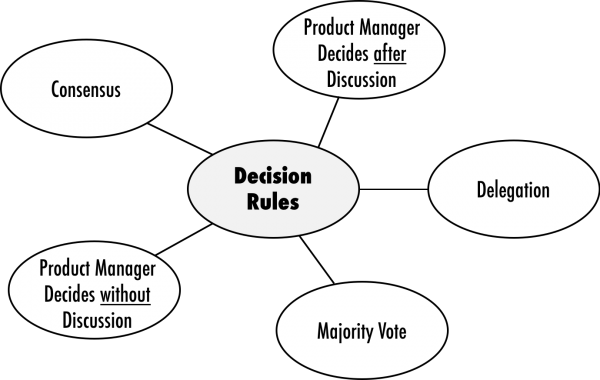

The following picture shows five common decision rules, which I’ve adapted from the book “The Facilitator’s Guide to Participatory Decision-Making” by Sam Kaner et. al. Note that in the picture, I use the term product manager to refer to the person in charge of the product. This does include product owners, of course.

Each decision rule in the picture above has its benefits and drawbacks. No single approach is always appropriate. To choose the right decision rule consider what’s at stake and how quickly the decision must be made, as I explain below.

Make sure that you involve the right people in the decisions. As a rule of thumb, engage with the players—the stakeholders with an interest in your product and the ability to influence its success—particularly when the stakes are high.

Consensus

Deciding by consensus means that everyone required to make the decisions agrees with the proposed solution or idea. A consensus-based decision creates strong buy-in and shared ownership, and it leverages the collective creativity and knowledge of the people present—everybody involved contributes to the decision. It is particularly helpful when the stakes are high and you make a strategic product decision, for example, if you should pivot, create a product variant to address new market segment, or change the goal of the next major release on the product roadmap.

The drawback of this approach is that it can take a comparatively long time to reach consensus within a group, as it requires developing a mutual understanding and evaluating competing ideas. You may even have to schedule several meetings to come to a conclusion, particularly if you test different ideas as part of the process.

Watch out that a consensus-based approach does not degenerate into decision by committee where people agree on the smallest common denominator and broker a weak compromise. This is unlikely to result in a sustainable agreement and translate into a successful product. As the saying goes, “a camel is a horse designed by a committee.” Consensus, instead, means that everybody is happy with the decision and wholeheartedly supports it.

When applying this decision rule, you will benefit from an experienced facilitator who guides everyone through the decision-making process and helps people reach agreement. Your ScrumMaster or agile coach might be able to help you with this.

Product Manager Decides after Discussion

This decision rule requires you to discuss an idea or solution with the right people and poll them for their opinions as well as any data that backs them up. Once enough discussion has taken place or the time is up, you decide. A good example would be deciding how to evolve the product backlog. You may ask the stakeholders and development team for their input, but after some discussion you might decide if new stories are added or not, and how to prioritise them.

The benefit of this approach is that it involves people in the decision-making process, but you retain control over the decision. It can also speed up the process by limiting the time spent to look for an inclusive decision. But the decision rule’s drawback is that people may not agree and support your decision—or worse, they might be frustrated as their suggestions were not taken on board. If the decision turns out to be wrong, then people may regard it as your mistake and your problem. Consequently, they may be reluctant to help you. The rule also requires that you have the authority to make the decision, which might not the case particularly for high-impact decisions that affect revenue and other business goals.

Apply this rule when you need to involve the development team and stakeholders to benefit from their knowledge or make them feel valued but at the same time, you must make the decision rather than allowing the group to reach agreement. This can be case when the key stakeholders don’t have the knowledge or willingness to come to a meaningful consensus or when speed is more important than reaching a sustainable agreement and generating strong buy-in, for instance, in a crisis.

Delegation

Delegate a decision if others are better qualified to decide or if your input is not needed. As the person in charge of the product, you would typically expect that the development team takes care of all technical decisions. But you might also delegate decisions about how to refine some of the user stories to the team, if people have enough knowledge about the users, the product, and how to create new stories.

Delegation helps ensure that the best qualified people decide, and it frees up your time: you don’t spend more time making decisions than necessary. When applied correctly, it also sends a positive signal to the appointed decision makers: it shows that you trust them and value their expertise.

But don’t use the rule to avoid difficult decisions. It can be all too easy to delegate a decision that you don’t want to be responsible for. And do not try to influence the group tasked with making the decision, for example, by saying, “you decide, of course, but I think we should do make the stories too small,” as this is a sign of mistrust. If you need to be involved in the decision, then do not delegate the decision to others.

Majority Vote

As its name suggests, majority vote means that most of the people required to decide agree with the proposed solution or idea. Applying this rule is simple and comparatively fast. But it creates a win-lose situation that can leave the minority frustrated and unwilling to support the decision.

I therefore recommend that you use this rule for product decisions only if the stakes are not high. Asking the key stakeholders to vote on a major strategy change would probably not be appropriate, and you would be better off using consensus or product manager decides after discussion.

If, however, you cannot agree within the Scrum team if a technical or user-related risk should be addressed in the next sprint, for instance, then you may want to ask people to cast their vote. This speeds up the decision-making-process and gets sprint planning done within its allocated time box; and it’s acceptable as the decision’s impact is likely to be limited: you’ll find out at the end of the next sprint if you’ve addressed the wrong risk.

Product Manager Decides without Discussion

As the person in charge of the product, you don’t have to involve others in all your decisions, of course: There are lots of low-impact decisions that you can and should make on your own. For example, is the sales rep required in the next sprint review meeting and should you invite the individual? Should you start breaking down some of the larger epics in the product backlog or hold off for another sprint? Should you move from monthly strategy and roadmap reviews to quarterly, as the product has stabilised?

Be aware, though, that this decision rule will only help you if you have the right knowledge to make the decision and you don’t need the buy-in from others. Take the last example from above where you decide to change the frequency of the product strategy reviews. If you are certain that the stakeholders will agree with your decision and if you don’t need their input or advice, then just decide. But if in doubt, use consensus or product manager decides after discussion instead. And if you use the approach for important decisions that have a significant impact on others, people may regard you as an autocratic leader and undermine or oppose your decisions.

Learn More

You can learn more about effective decision-making and using the right decision rule by attending my product leadership workshop.

You may also find it beneficial to read the book “The Facilitator’s Guide to Participatory Decision-Making” by Sam Kaner et al., which has some great advice on building sustainable agreements, although it’s not specific to product management.

| Reference: | Decision Time: How Decision Rules Help You Make Better Product Decisions from our JCG partner Roman Pichler at the Pichler’s blog blog. |