Making Consensus-based Product Decisions

Consensus is a powerful approach to generate strong buy-in and shared ownership of a decision. But it can be challenging to apply and if used incorrectly, it can create mediocre results. This post helps you leverage consensus to make successful product decisions. It explains when and how to use it, and it discusses common traps and how to avoid them.

Benefits and Limitations

Deciding by consensus means that everyone required to make the decision agrees with it. Applied correctly, it results in a better decision and creates strong buy-in and shared ownership. It is particularly helpful when the stakes are high and you have to make a complex product decision, for example, if you should pivot, create a product variant to address new market segment, or change one of the goals on the product roadmap.

Consensus is certainly not a silver bullet. Do not use it if:

- You face an emergency and a decision must be made quickly, for example, when you are in danger of missing a critical release date;

- The decision is low impact and no big deal;

- The people who need to contribute to the decision are not willing to collaborate.

Choose a different decision rule instead, as I explain in my post “Decision Time: How Decision Rules Help You Make Better Product Decisions.”

To take full advantage of consensus, you require a collaborative mindset, a participatory decision-making process, and a technique to help you understand if you have found a solution that everyone agrees with.

Mindset

Consensus comes from the Latin verb “con-sentire.” Con means “together,” and sentire is commonly translated as “to feel, perceive, think.” To reach consensus, people must understand each other’s perspectives and feel and think together. This, in turn, requires that everybody involved in making the decision is heard and listened to. What’s more, people must have an open mind and let go of their preconceived notions and ideas, appreciate other people’s ideas, and jointly look for opportunities to discover with new, better ideas.

If the individuals cling to their ideas and believes, if they think that they know best and that their ideas should win, or if they act in selfish ways and want to get the best deal for themselves or their department, then the group will struggle to reach consensus.

As the person in charge of the product, you should lead by example and demonstrate the right attitude, be collaborative and appreciate ideas even if they sound unconventional. You may also benefit from involving an experienced ScrumMaster, coach, or facilitator who helps you with setting the ground rules and facilitates the discussion.

Process

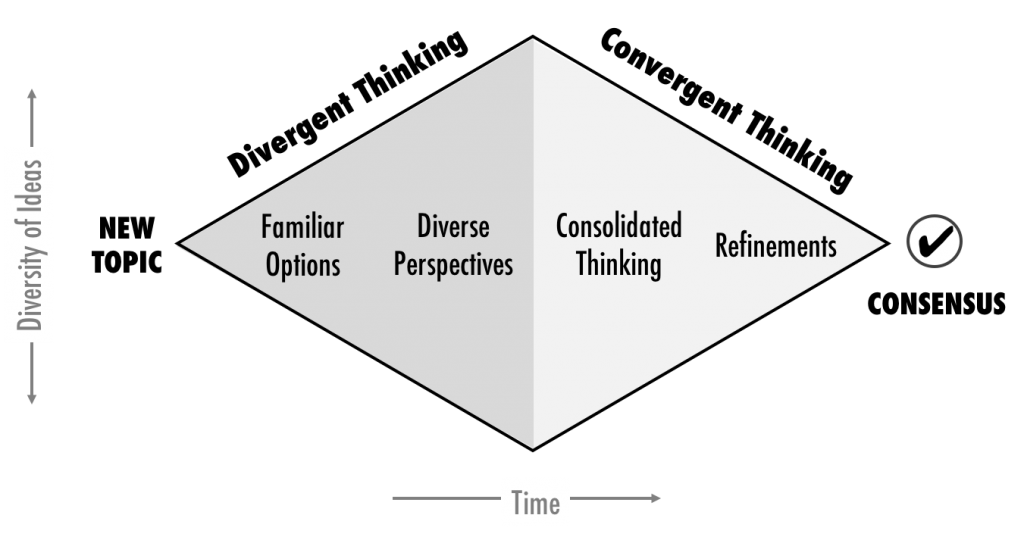

Deciding by consensus can take time and involve an element of struggle, particularly when you make a complex decision: Everyone required to contribute to the decision must have the opportunity to equally share their ideas and perspective, and the group must use diverse thinking. Only after that’s happened can you start looking for common ground and convergence. The picture below depicts this approach, which is based on “The Facilitator’s Guide to Participatory Decision-Making” by Sam Kaner et. al.

At the start of the decision-making process depicted above, encourage people to generate different ideas and share diverse perspectives using free-flowing open discussion or structured brainstorming, for example. Suspend judgment at this stage and don’t criticise the ideas. You want to generate plenty of diverse suggestions before you evaluate them.

Resist the temptation to prematurely reach agreement. Otherwise you may end up with a mediocre solution based on familiar options and weak buy-in. In the worst case, you experience design by committee where people broker a weak compromise—which is the opposite of what a consensus-based product decision should deliver!

Ensure that everybody fully participates and don’t allow individuals to dominate. Otherwise you won’t be able to leverage the collective creativity and knowledge of the group, and the decision-making process might get highjacked by the HIPPO and the “consensus” decision dictated.

Once everybody has been heard, take the next step. Encourage people to understand each other’s perspectives and motivations and look for common ground. This is likely to involve some struggle, as some individuals—possibly yourself—may still be attached to their ideas. Give them time to let go and embrace other people’s suggestions. Consider testing some of the ideas by running experiments—be it observing or interviewing users or exposing prototypes to them. Sort ideas into categories, distinguish opinions from facts, and summarise key points. A great solution often combines elements of different ideas, and it can significantly vary from what you had in mind at the beginning of the process. Finally exercise judgement using the data that you have collected and come to agreement.

Participating in this process can be difficult: it requires that people tolerate ambiguity, constructively deal with conflict, let go of their own ideas, and embrace someone else’s suggestion. Choose a safe, comfortable environment; don’t rush the process and allow for enough time; and involve a skilled ScrumMaster or coach who helps you guide people through the process.

Agreement Scale

One of the challenges of a consensus-based approach is to understand if you have found an inclusive solution and reached agreement, or if you need to continue the process and do more work. An agreement scale helps you with this.

| 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| I whole-heartedly endorse it | I agree with minor reservations | It’s not great but I can support it | I disagree | I veto the proposal. |

The scale above shows five gradients of agreement. The range from whole-hearted endorsement to vetoing the proposal. You can use more gradients if you wish to, but I find that in practice five, the options above are sufficient.

With your scale in place, ask everyone to express how much they agree. A technique commonly used on an agile teams is the fist of five. Individuals express their agreement by showing the appropriate number of fingers, for example, five fingers for whole-hearted endorsement and one finger for veto. An alternative I like to use is asking people to dot-vote and stick or draw a dot underneath the appropriate number, which nicely visualises the group’s level of agreement.

If everybody whole-heartedly endorses the proposed decision, then you have unanimous agreement. That’s great but often not necessary. I find that it is OK when some people agree with minor reservations. But if several individuals are neutral (gradient three) or can’t support it, then you should continue the discussion and look for a solution that everyone can agree with.

If you find that this is taking too long and you are running out of time, then I recommend changing the decision-making rule. As the person in charge of the product, make the decision based on the input you have received so far, or use majority vote and let the group decide. Bear in mind, though, that these two approaches will not generate the same level of buy-in and ownership, and don’t forget to communicate the change to the group.

| Reference: | Making Consensus-based Product Decisions from our JCG partner Roman Pichler at the Pichler’s blog blog. |